What Is Sharecropping?

A Rural Economic Strategy Extends the Pre-Civil War Way of Life into the Twentieth Century

Overview

Sharecropping is an agreement between the person who owns the land and a laborer,

who works the land in return for a percentage of the profits at the end of the season.

Almost always, the sharecropper's wife and children were included in the agreement

and worked the land as well. Sharecroppers in the U.S. have been of varying races,

but in the South, they were predominantly African-American.

Sharecropping is an agreement between the person who owns the land and a laborer,

who works the land in return for a percentage of the profits at the end of the season.

Almost always, the sharecropper's wife and children were included in the agreement

and worked the land as well. Sharecroppers in the U.S. have been of varying races,

but in the South, they were predominantly African-American.

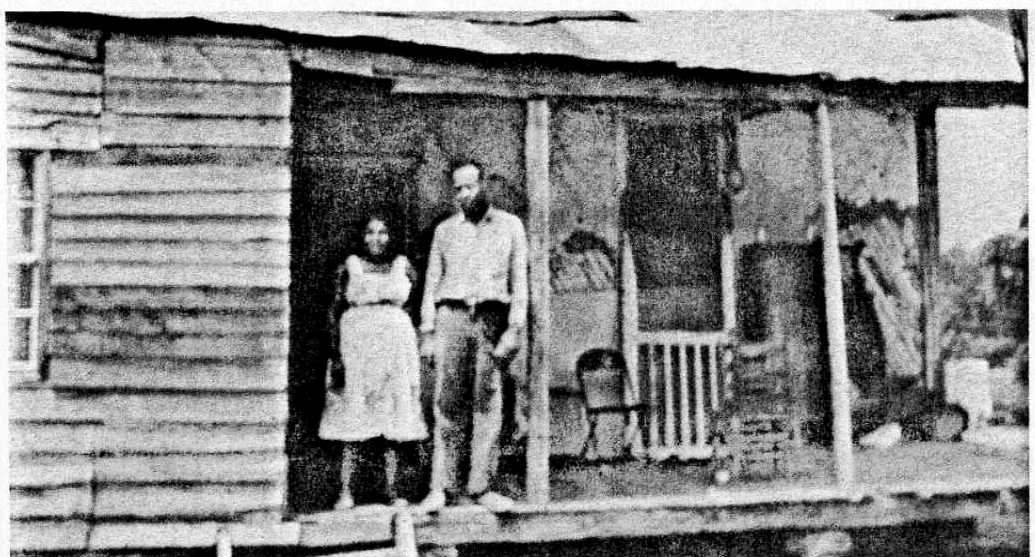

Fayette County home. c. 1964. Source: Fayette-Haywood Newspaper.

Harpman Jameson describes Sharecropping

2002 Documentary Project on Fayette County, Tennessee. Source: Special Collections, University of Memphis Libraries.

Theoretically, sharecropping might seem like a workable solution for a farming need—one that offers an equal exchange: The landowner would provide seeds, fertilizer, tools, and housing, in return for a sharecropper's labor. At the end of the season, the profits from the harvest would be split between the sharecropper and the landlord. However, in Fayette County, as in most of the South, the landowners held all of the economic power in sharecropping relationships, and could take advantage of the sharecroppers, who often knew no other way of life and lacked alternative means of making a living. In Fayette County, the terms sharecroppers agreed to were often unknown or misunderstood because of low literacy rates and the verbal nature of the contracts. And sometimes, when it came time to settle accounts, the terms were simply ignored—in the landowner's favor.

Most sharecroppers lived with their families in small, unsafe homes. |

Post-Civil War, white landowners in the South scrambled to run their plantations profitably—only now, without slaves. Despite the fact that courts deemed sharecropping a vestige of slavery in an effort to enforce civil rights laws after reconstruction, sharecropping remained a pillar of Southern economy. In 1865, the 13th amendment to the US constitution made slavery illegal. However, from 1880 to 1890, Fayette County experienced a 50% increase in the number of sharecroppers [2].

To maintain a steady source of cheap labor and to continue the well-established, patriarchal

relationship comfortable for whites in the rural South, it was in the best interest

of the landowners to keep their sharecroppers dependent on them. As a result, landowners

also kept the sharecropper population powerless. From the seeds for planting crops

to the humblest everyday necessities, sharecroppers had to go to their landowner,

hat in hand. It is no wonder that critics have called sharecropping "semislavery"

[3].

To maintain a steady source of cheap labor and to continue the well-established, patriarchal

relationship comfortable for whites in the rural South, it was in the best interest

of the landowners to keep their sharecroppers dependent on them. As a result, landowners

also kept the sharecropper population powerless. From the seeds for planting crops

to the humblest everyday necessities, sharecroppers had to go to their landowner,

hat in hand. It is no wonder that critics have called sharecropping "semislavery"

[3].

Today, it is difficult for us to truly understand the dire implications of this system: Even through much of the 20th century, conditions in the rural South remained almost the same as they had been for the past two centuries. A low-yield season would leave the sharecropper unable to pay back the landlord for resources advanced at the beginning of the season. Additionally, sharecroppers were unable to repay loans made over the year for necessities he and his family could not grow, raise, or build for themselves, such as health care, fuel, shoes, seeds, and paint. It was common for expenses of the sharecroppers to be rigged when tallied so that, even in a good year, the sharecropper might barely make a profit or even remain in debt to the landowner. This practice left sharecropper families dependent on white landowners for generations.