Windsor Secures NSF Grant

Investigating the way world leaders think and communicate

An interdisciplinary research team led by Dr. Leah C. Windsor received a $450,000 grant from the National Science Foundation to study the communication patterns of international relations. Windsor is an associate professor in the Department of English (Applied Linguistics) and the Institute for Intelligent Systems. Co-PIs on this grant include Dr. Shaun Gallagher and Dr. Deborah Tollefsen from the Department of Philosophy, Dr. George Deitz from the Department of Marketing in the Fogelman College of Business, Dr. Miriam van Mersbergen from the School of Communication Sciences and Disorders, Dr. Nicholas Simon from the Department of Psychology, and Dr. Alistair Windsor from the Department of Mathematical Sciences and the Institute for Intelligent Systems.

The research team represents six different disciplines across three colleges and schools. The team currently has two articles under review from this project: one about multimodal cues to deception; the other about the process of grant-writing and the role of mentorship. It is important to note that this grant was written and submitted during the global COVID-19 pandemic, and then-graduate student Dr. Christian Kronsted was instrumental in preparing and assisting with the grant-writing process.

The project overview

Human beings are not computers. Nor do we think like computers. Rather we think with our whole entire body - and world leaders are no exception. This new and exciting project at the Institute for Intelligent Systems uses the groundbreaking embodied cognition framework to investigate the way world leaders think, communicate, - and lie. The project examines multimodal communication; the way the whole body is involved when we communicate. Gestures, eye blink activity, body language, tone of voice, neuronal activation patterns, even how much someone sweats; the whole body is in use when we communicate and the project intends to measure and cross compare all of this rich data. For example, what is the relationship between how slowly someone blinks and truth telling? In an initial pilot study for the project, it was found that former President Bill Clinton not only kept his eyes open for much longer when lying, he also deployed different gestures, and the pitch of his voice even changed.

The project breaks new ground in several ways. It is the first of its kind to create a multimodal data set using a combination of computational linguistic analysis, multimodal signals derived from audio and video analysis, and biometric audience data. To date, multimodal analyses have not been deployed comprehensively on a representative international corpus. Furthermore, this project is one of the first to take the embodied cognition framework and apply it concretely to a major case study. While various corners of cognitive science research have looked at the relationship between communication, gestures, and the biometrics, our project is the first to cross overlay a wealth of biometric, linguistic, auditory, and visual data into one coherent framework. This project is interdisciplinary in every sense of the word.

The project cross compares a wealth of embodied data to analyze the way world leaders think and communicate on the public stage. This data will not only give us insight into the meaning behind the words it also tells us something about the stability or instability of a political regime; leaders with authoritarian tendencies communicate differently than more democratically inclined leaders. The embodied cognition approach is especially beneficial for understanding politics in opaque environments, like authoritarian regimes, where it is difficult to observe true preferences and priorities of leaders. In short, if they tell us one thing, but mean another, how do we know what they are really after? Given seismic changes in the international system, including resurgent populism, and the rise and demise of regional and global regimes (such as the United Kingdom and Brexit, and the growing influence of China and Russia within Asia and abroad), the project provides a way for scholars to better understand problems like state stability, conflict processes, and regime transition. A multimodal approach to analyzing the international system will help us know more than what leaders’ words alone convey.

It is not easy getting data from world leaders. While there is no lack of world leaders recorded on video, these recordings are from vastly different arenas of communication. To keep the data uniform the project will at first, focus on recordings of world leaders giving speeches at the United Nations General Assembly. These speeches tend to be roughly the same length, with the same background, and in the same controlled setting. Thus, the UNGA provides a wealth of data for the team to study. For example, using advanced software the team can overlay the acoustics of the speaker's voice with their facial expressions, eye blink rate, and their gestures. In Figure 2 we see a data example from the 2012 speech by Iranian President Ahmadinejad at the United Nations.

Figure 1. Ahmadinejad at the United Nations, 2012. For a full video: http://tinyurl.com/y9js8toa

The United Nations speeches are also fruitful data since we can often compare the words of the speaker to their political actions “back home” pre and post speech. Communication is not just a one way street; world leaders communicate because they have an audience. Hence, the second part of the project is to measure the biometrics of political speech viewers. So while we cannot put an EEG cap on a world leader, we can measure brain activity of those who watch his speeches. Similarly, we can measure their galvanic skin response (electric conductivity on the skin that changes depending on excitement), track their eye movements as the watch the speech, and a wealth of other data. Getting biometrics from viewers of speech will allow the team to understand the embodied responses that takes place between viewers and speakers in deliberately political communication. Below is an image of a research setup that tracks the participants eye movements, their galvanic skin response, and neuron activation patterns as they watch a video. In this case participants will watch political speeches, some with and others without deception.

Figure 2. Suite of audiovisual instruments for experiment with subject

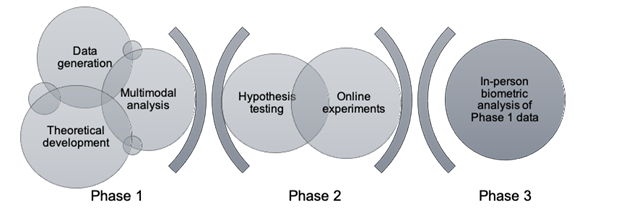

Project phase

Figure 3. Relationships between Phases 1, 2, and 3

In Phase 1 (Year 1), we will explore the following questions: How does the communication style of world leaders emerge from embodied cognitive processes? What multimodal signals indicate changes in cognitive load (i.e., stress, deception, emphasis, discomfort)? How does the UNGA environment facilitate (or constrain) multimodal style matching? If the UNGA general debate occurs in a virtual environment this year, what differences may we observe in the multimodal communication styles of leaders given the audience-free digital environment? What systemic changes can multimodal features help us understand better, i.e., conflict and cooperation?

This project will facilitate the understanding of the importance of multimodal signals by providing a queryable data set, pedagogical materials about multimodal analysis for non-technical audiences, academic publications to translate the meaning of multimodal inputs for a wider audience, and policy papers and opinion editorials to reach a broader non-academic audience. This will substantially improve the scientific community’s understanding of how multimodal channels work in concert with language to convey meaning, especially in international and multicultural contexts.

In Phase 2 (Year 2), we will solicit a representative international sample of participants through Mechanical Turk and YouGov to provide feedback on video and audio clips from leader speeches at the UNGA. We will select the participants from a representative geographic, cultural, and linguistic sample[i]. Using data generated in Phase 1, we will isolate video clips for participants to evaluate. The research questions associated with Phase 2 are as follows: How do native speakers of the language and culture interpret the UNGA speeches? What processes and features make leader's speeches persuasive to viewers? Do native and non-native speakers share interpretations, or are they divergent?

Phase 3 (Year 3) will involve in-person human subjects research, including how world leaders’ communication is perceived, contextualized by the demographics and pre-existing beliefs held by the viewer. Viewer effect will be determined by robust biophysical indicators (galvanic skin response, pupillometry, eye-tracking, EEG) that will capture biophysical responses, attention, and cognitive loads in an experimental laboratory setting. The research questions for Phase 3 include the following: In terms of biophysical indicators, what multimodal features of communication are most persuasive for viewers? In what ways do the embodied cognitive processes identified in Phase 1 align with the expected viewer response when measured empirically? Figure 2 shows the current capabilities among collaborators on this proposal for evaluating biophysical markers in subject participants in the laboratory setting.

Early findings

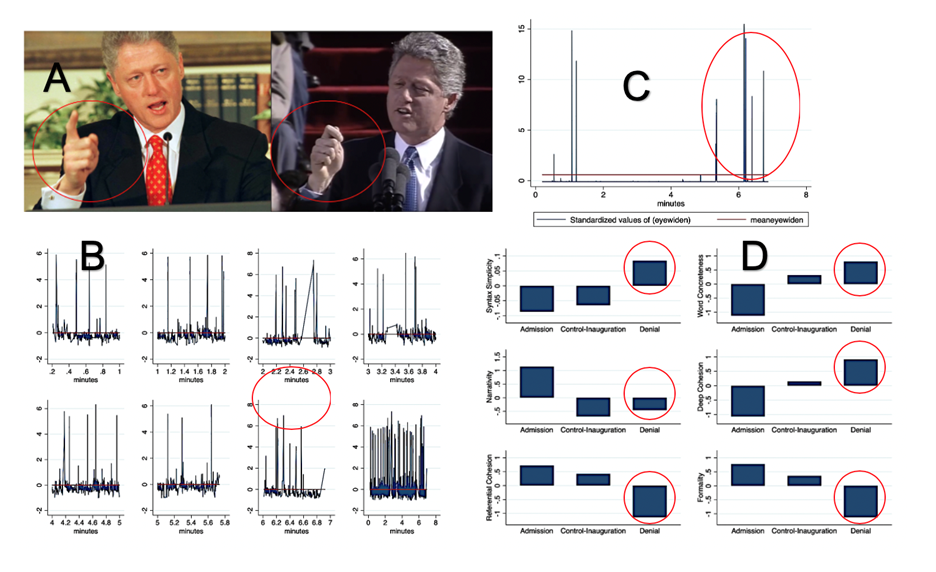

As a proof of concept, we analyzed a policy speech given by President Clinton, where he also provided extemporaneous communication about his relationship with the former White House intern, Monica Lewinsky. One of the essential components of undertaking multimodal research is to establish a baseline pattern to compare the behavior of interest to. The first seven minutes of the speech focused on after school care for children in the United States, while the last minute was his denial of an inappropriate relationship. We find that his blink rate, voice acoustics, gestures, and language patterns differ substantially from the control portion to the deception portion of the speech.

Figure 4. Multimodal analysis of President Clinton's communication

Commitment to mentorship and broader impacts

This project will facilitate the understanding of the importance of multimodal signals by providing a queryable data set, pedagogical materials about multimodal analysis for non-technical audiences, academic publications to translate the meaning of multimodal inputs for a wider audience, and policy papers and opinion editorials to reach a broader non-academic audience. This will substantially improve the scientific community’s understanding of how multimodal channels work in concert with language to convey meaning, especially in international and multicultural contexts.

Further, this project will benefit minority and underserved communities, such as women in computational social science and STEM fields, as The University of Memphis has a robust existing network to recruit and connect with these students.[i] As a part of the NSF’s mission to reach traditionally underserved communities and minorities, we engage in concerted mentorship which is integral to retaining women scholars in academia.

For more information: https://sites.google.com/view/leahcwindsor/

Team

Dr. Leah Windsor is an associate professor in the Department of English (Applied Linguistics) and in the Institute for Intelligent Systems at The University of Memphis. She received her Bachelor of Science in Linguistics from Georgetown University in 1998 and her Ph.D. in Political Science from The University of Mississippi in 2012. She directs the Languages Across Cultures and Languages Across Modalities labs.

Dr. Alistair Windsor received his Ph.D in Mathematics in 2002 from the Pennsylvania State University and is the director of the Institute for Intelligent Systems and an associate professor in the Department of Mathematical Sciences. He has extensive experience using data science to study educational interventions and to evaluate large scale projects including NSF projects totaling more than $2.5 million.

Dr. Miriam van Mersbergen is assistant professor in the School of Communicative Sciences and Disorders at the University of Memphis. She directs the Voice Emotion and Cognition Laboratory, which uses a multidimensional approach to investigate how emotional experience and cognitive factors influence vocalization and communication.

Dr. Shaun Gallagher is the Lillian and Morrie Moss Professor of Philosophy with the philosophy department at The University of Memphis. He is one of the world’s leading experts in embodied cognition with seven books and hundreds of articles on the topic.

Dr. Deborah Tollefsen is a professor with the philosophy department at the University of Memphis and the associate dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. Her research and teaching interests include philosophy of mind, social epistemology, and social ontology. She has a Ph.D. from Ohio State University and a MA from the University of South Carolina.

Dr. Nicholas Simon is an assistant professor of Psychology at the University of Memphis. His research laboratory investigates the neurobiological basis of motivated behavior, with a focus on the evaluation of costs and benefits during decision-making. He has extensive experience with processing and interpreting neural data.

Dr. George D. Deitz is a professor in the department of Marketing & Supply Chain Management. He received his Ph.D. in Marketing in 2006 from The University of Alabama. He also holds a M.S. in Sport Management, a B.S. in Marketing, and a B.A. in English Literature degree from West Virginia University. He is the founding director of the Customer NeuroInsights Research Lab (C-NRL) at The University of Memphis.

Dr. Christian Kronsted received his Ph.D. in 2021 in Philosophy from The University of Memphis.

[1] Raymond A. Noe, “Women and Mentoring: A Review and Research Agenda,” Academy of Management Review 13, no. 1 (1988): 65–78; Jacob Clark Blickenstaff*, “Women and Science Careers: Leaky Pipeline or Gender Filter?,” Gender and Education 17, no. 4 (2005): 369–86; Lisa Tsui, “Effective Strategies to Increase Diversity in STEM Fields: A Review of the Research Literature,” The Journal of Negro Education, 2007, 555–81; Valerie J. Morganson, Meghan P. Jones, and Debra A. Major, “Understanding Women’s Underrepresentation in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics: The Role of Social Coping,” The Career Development Quarterly 59, no. 2 (2010): 169–79; Sara McLaughlin Mitchell and Vicki L. Hesli, “Women Don’t Ask? Women Don’t Say No? Bargaining and Service in the Political Science Profession,” PS: Political Science & Politics 46, no. 2 (2013): 355–69; Marijke Breuning and Kathryn Sanders, “Gender and Journal Authorship in Eight Prestigious Political Science Journals,” PS: Political Science & Politics 40, no. 2 (2007): 347–51.