THE ROOTS OF FOOD DESERTS

By Ryan Jones

For most individuals reading this article, it is not difficult to find fresh and healthy food.

In Memphis, one can drive along Poplar Ave. from downtown all the way to Collierville and find full-scale grocery stores within a one-to-two-mile radius of one another along the entire route. But if you were to venture north or south, into areas like South Memphis, Orange Mound, Binghampton, North Memphis, Whitehaven or Frayser, you’d face a much more difficult task in finding anything resembling a full-service grocery store. You’re more likely to discover streets packed with fast food options, dollar stores with limited fresh food inventory and a plethora of corner stores packed with cold cuts, junk food, alcohol and an assortment of overpriced loaves of bread and gallons of milk.

These areas of town are what have become known as “food deserts,” communities that have poor access to healthy and affordable foods. They are usually concentrated in low-income and historically marginalized areas throughout the country, with issues of longtime systemic racism, racial residential segregation, poor access to transportation and economic inequality woven into the history of these barren food landscapes.

A recent study by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) says that 39.4 million

Americans live in low-access communities, or communities in which at least a third

of the population live in a food desert. The families living in these areas are 2.28

times more likely to have to travel further distances to supermarkets than middle-class

families, a problem which is exacerbated when many of these families do not have access

to a car or are dependent on unreliable public transportation. Even further, Black

people are 2.49 times and Latinx people are 1.38 times more likely than white people

to live in neighborhoods without access to a full-service grocery store.

The story is no different here in the Mid-South.

In Memphis, which is approximately 62 percent African American, the situation plays out about as you’d expect. The USDA interactive atlas and map shows various overlays of food insecurity, access issues and other key demographics of a certain city or county in America. Examining this map, it is clear to see that the city’s poorest zip codes are also the most food insecure. They are in the deepest food deserts in the region, with less means to escape.

The latest report from Feeding America, a national hunger-relief organization, shows that 115,980 residents in Shelby County were classified as food insecure in 2019 (the last year of data collection), which means that about 12.4% of the population faced a “lack of access, at times, to enough food for an active, healthy life for all household members and limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate foods.”

Even more striking, the child food insecurity rate in Shelby County from this report comes in at 19.8%, meaning there are more than 46,000 children in Shelby County suffering from food insecurity at the time of this report.

But it’s about more than just food. In Memphis, and across the country, these food deserts equate to life and death. A healthier diet and lifestyle mean, generally, a longer life. In impoverished neighborhoods located in food deserts, fresh food and a healthy diet are often more dream than reality, which means these residents are facing a variety of health problems as a result.

“FOOD SECURITY SHOULD

BE THE BEDROCK OF

SOCIETY'S FUNCTION."

-DR. LEANNE DESOUZA-KENNEY

In the wealthiest part of the greater Memphis region, people live on average 13 years longer than in the poorest communities.

Should access to fresh and healthy foods really be a debate over whether it is a privilege or a human right? Should the profits of a grocery store and the food industry take precedence over the lives of impoverished citizens?

HOW DID WE GET HERE?

This is a deceptively complex question and one that has a number of equally complex answers.

Talking about food deserts involves touching on everything from food insecurity, cultural norms, economics, capitalism, race, education, public policy, antitrust matters and business practices, just to start with.

Food deserts are at the complex intersection between poverty, food inaccessibility, systemic racism and health.

One of the largest combination of reasons food deserts exist, in Memphis and across the country, deals with race, economics and public policy.

The (Not so) Thin Red Line

The largest item to come out of that cross- section of reasons is “redlining.” And you can’t talk about the history of redlining without mentioning segregation. These two concepts, almost more than any other, have contributed to the creation and proliferation of food deserts on a national scale.

The concept of redlining was a racist practice used mostly by government agencies and banks to deny services, most notably mortgages, in majority Black inner-city neighborhoods. The practice made Black homeownership difficult by targeting certain communities as being too risky to invest in.

“If it was deemed to be a neighborhood where they did not want to encourage investment, it was considered hazardous and colored red on a map,” said Ennis Davis, an urban planner at the organization Modern Cities. “Essentially, across the U.S., every majority-Black neighborhood in a city at that point in time became red.”

It started in the 1930s with policies and organizations formed under President Roosevelt’s New Deal. The policies continue to influence living patterns, business spending and location and poverty trends today.

In 1933 the FDR presidential administration established the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) to provide low-interest mortgages. The HOLC incorporated racially discriminatory criteria into its lending requirements and deemed those living in racially or ethnically mixed neighborhoods “too risky” for loans. In subsequent years, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and the Veteran’s Administration (VA) also adopted lending standards based on the ones used by the HOLC. The FHA developed an infamous tool called the Underwriting Manual of the Federal Housing Administration, which specifically said that “incompatible racial groups should not be permitted to live in the same communities,” and “if a neighborhood is to retain stability, it is necessary that properties shall continue to be occupied by the same social and racial classes.”

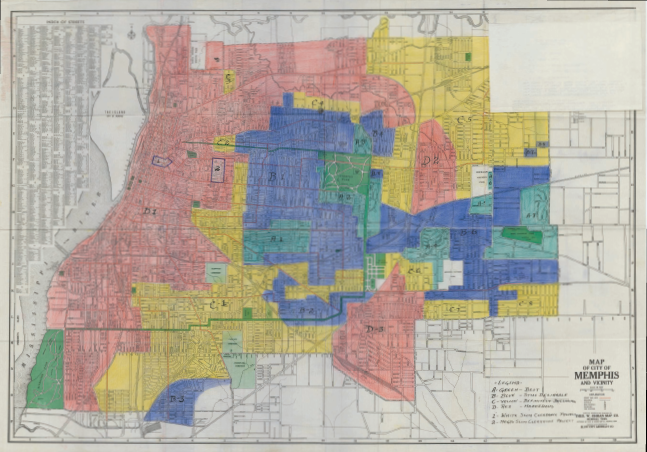

“Redlining” as a term comes from the work done by the HOLC and the federal government, as they developed maps of every metropolitan area in the entire country and color-coded them to indicate where it was safe to insure mortgages. Anywhere African Americans lived, and anywhere African Americans even lived nearby, were colored red to indicate to appraisers that these neighborhoods were too risky to insure mortgages. They’d been redlined.

Examining these maps today shows just how overtly racist they were.

One redlined neighborhood deemed “hazardous” gives the reason as “Infiltration of: Negroes.”

Another summary for a neighborhood in Richmond, Va., with a B- rating reads as “Respectable people but homes are too near negro area.”

"This is considered the most exclusive, or swank, section in Springfield," says the entry for one of the city's two A-classified neighborhoods. "The area is high restricted" meaning it enforces strict rules barring non- white people from buying houses there.

The HOLC map for Memphis even has category designations showing where “Negro Slum Clearance Projects” were located throughout the city, in order for appraisers to knowingly avoid those areas.

Overlaying this 1940s Memphis redline map with the most impoverished zip codes of today also shows that these redlining efforts had a generational effect on resident’s poverty levels.

Aside from some improvements to the downtown and midtown areas, much of the area’s marked as hazardous or “definitely declining” on the redline maps are still entrenched in poverty today.

Robert Nelson, director of the Digital Scholarship Lab at the University of Richmond, was one of the designers of the digitization project that uploaded all HOLC redline maps and converted them to online interactive maps on a website that embeds all archived documents on a single map of the USA. Selecting a specific city reveals the archived HOLC map images and zooming in shows a color overlay over a modern map with street names and building outlines.

As a result of redlining, families of color "couldn't avail themselves of what is arguably the most significant route to family and personal wealth-building in the 20th century, which is homeownership," according to Nelson.

Redlining is frequently cited by scholars examining American inequality, and it was highlighted by Ta-Nehisi Coates in his recent "Case for Reparations" piece in The Atlantic.

"Neighborhoods where black people lived were rated "D" and were usually considered ineligible for FHA backing," he wrote. "Black people were viewed as a contagion. Redlining went beyond FHA-backed loans and spread to the entire mortgage industry, which was already rife with racism, excluding Black people from most legitimate means of obtaining a mortgage."

Without access to FHA-insured mortgages, he writes, black families who sought homeownership were forced to turn to predatory and abusive lenders.

“Studies have indicated that there are often biases against opening stores in communities of low-income and minoritized individuals based on a perception of lower profit margins,” according to Brad Shugoll, associate director of service and leadership at the Wake Forest Office of Civic and Community Engagement.

“This has amounted to structural racism and what some have called ‘supermarket redlining.’”

Urban Renewal & Bad Zoning

Additional federal and local government policies and regulations continued to influence the patterns of minority settlement throughout cities in the U.S. even after the New Deal.

In an effort to fight “white flight” out of cities and into the suburbs in the 1950s, the Housing Acts of 1949 and 1954 were passed. Both of these Acts touted an “urban renewal” policy and signed off on funding to clear slums and build public housing. In urban centers across the country, the implementation of these policies meant that predominantly Black neighborhoods were being razed and cleared. In order to gain the federal funding to get rid of their “slums,” these cities had to guarantee affordable replacement housing for the displaced residents. This all-too- often meant that local authorities constructed multiunit projects that were packed with residents at an extremely high density. Cities placed majority African American public housing projects in African American neighborhoods, conforming to the racist sentiments of the time.

These federally funded and locally administered urban renewal policies became representative

of the starkly different treatment of Black and white populations by the government.

“Family public housing increasingly became a minority relocation program, while government

subsidies brought home ownership and suburban mobility within the reach of the white

middle class,” noted Arnold Hirsch in his work, "Searching for a ‘Sound Negro Policy’:

A Racial Agenda for the Housing Acts of 1949 and 1954."

Zoning policies were another contributing factor to the continued segregation and isolation of these marginalized communities, resulting in further removal from quality food sources, equal education opportunities and career advancements. These zoning policies predated the urban renewal movement and contributed to the segregation patterns we still see in existence today. After the U.S. Supreme Court found that discriminatory zoning practices were unconstitutional in the case of Buchanan v. Warley, where the Court held unanimously that a Louisville city ordinance prohibiting the sale of real property to Blacks in white- majority neighborhoods or buildings and vice versa violated the Fourteenth Amendment's protections for freedom of contract, cities turned to implicit ways of zoning against minorities. Many enacted ordinances that restricted home occupancy to nuclear families only, in order to discourage minorities more likely to live with extended family members. Some cities also started to restrict multi-family homes from being built in order to discourage low-income residency. Zoning ordinances have, and continue, to function as a way to influence the racial makeup of communities across the country.

There is a clear pattern in the history of our country of public policies and private discrimination shaping segregated living patterns. These patterns also show a strong correlation not only to the access to educational and employment opportunities, but ultimately to the health and nutrition of those living within these communities. Numerous studies have shown that low- income and minority neighborhoods, many of which have been shaped by these redlining and segregation-based zoning policies over the years, are much less likely to have access to large supermarkets and fresh foods.

But these food deserts were not created by redlining and zoning policies alone.

As those problems persisted, grocery stores themselves underwent an evolution that has in turn left impoverished communities searching for answers.

From Urban to Suburban – Where Did the Grocery Stores Go?

The Federal policies that drastically influenced the living patterns of minorities in cities across the country also affected the development of grocery stores in those same communities. As more and more middle-class white families moved out of urban centers to the suburbs, many businesses such as supermarkets moved with them. These businesses moved along the same geographical paths in order to take advantage of this middle-class spending, which consisted mainly of white families due to the redlining and zoning policies of years past.

The retail model for an urban grocery store and a larger suburban market proved to be drastically different. Upon relocating outside of traditional urban centers, these supermarkets shifted from a model that provided products through small, specialized stores like meat markets, bakeries and produce stores, to a model that brought together many, many different products all under one roof. This evolution of the supermarket came as a result of very inexpensive suburban land and very pro-business suburban zoning practices.

In 1950, the average supermarket size was approximately 25,000 sq. ft. Fast forward to today and grocery stores are typically looking at 40,000 to 45,000 square feet of land space in order to attain the volume and mix of products necessary to keep a store competitive in pricing. As these suburban supermarkets grew in size over the years, they were able to capture more and more of the suburban market. In contrast, city-centered supermarkets were more expensive to maintain and by the mid-90s, with a few exceptions, inner city markets were “virtually abandoned by leading chains,” according to research published in Economic Development Quarterly.

“For large corporations, they go into the wealthier neighborhoods where they can make a lot of money,” said Elena Delavega, a professor of Social Work at the University of Memphis, specializing in policy and global poverty, Memphis poverty, wages, taxes and social inequality. “They are more interested in having a lot of big profits than serving a community.”

The economic advantages to these larger suburban supermarkets were immediately evident. They were able to cultivate a great deal of buying power and get large quantities of goods at lower prices.

Additionally, some of these chains were so large that they were able to produce their own products in-house, meaning they could sell those at even steeper discounts while still keeping a high profit rate. They even had the advantage of complex logistical infrastructure and networks, which helped the larger chains and stores better forecast demand and plan their inventories accordingly.

Meanwhile, city-based supermarkets were faced with higher land costs, stricter residential vs. business zoning laws, noise regulations, pollution regulations and all around less business- friendly policies compared to the suburbs.

Another issue compounding problems for city- based groceries is commercial redlining and hesitancy of insurance companies to provide coverage to businesses located in Black or minority neighborhoods. According to research conducted by Economic Development Quarterly, businesses continue to suffer from the inability to get loans in the inner city “because of the limited attention that mainstream banks paid them, historically.” Additionally, these inner-city businesses often face higher than average insurance rates because of perceived or actual crime in urban areas. Many cities also have outdated policies in place that make it harder for urban grocery stores to open in areas encompassed by food deserts. For example, many cities have zoning ordinances that set higher requirements for parking for supermarkets relative to other businesses. This higher parking requirement in densely populated cities where land is more scarce makes it even harder for a supermarket to become a reality, combined with the other factors involved. Even where space is available, the increased parking requirement may be too expensive since new stores may be required to purchase land to accommodate more parking than would be justified by the demand.

That’s a lot for small urban grocery stores to compete with.

Which leads us to situations that we see in impoverished neighborhoods across cities like Memphis. Corner stores, gas stations and convenience stores serving as communities’ only fresh food options.

These types of stores are not burdened by higher parking requirements and other factors, but the price neighborhoods pay is less fresh food, perishable items or healthy options.

MODERN-DAY MEMPHIS CLOSURES

Grocery stores are always hot topics of discussion in Memphis. Articles about the mere hint of a new grocery store are always some of the most read, clicked and shared across all local media platforms.

As of this writing, a long- awaited grocery store, though smaller than a big-box retailer, is finally opening in downtown Memphis in the upscale South Main neighborhood to an incredible amount of media attention and fanfare.

But for all of the topic’s popularity and recent success stories, there have been numerous sad stories of closures and increased food insecurity in the past several years that only highlight the still timely and relevant issue of food deserts here.

As recently as 2018, Kroger closed two of its local stores in two of Memphis’ majority African American neighborhoods within weeks of each other. The location in the Southgate shopping center in South Memphis closed in February 2018, immediately followed by the closing of the location on Lamar Ave. in Orange Mound. At the time, Kroger announced that the two stores had losses of nearly $4.8 million over the past three years. Both locations had served their respective communities for years, with the Lamar location operating since 1985, replacing another nearby store that had opened in 1954.

At the time, Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland shared the disappointment of area residents, saying “I'm disappointed by Kroger's decision to close two stores in Memphis. But these neighborhoods are no less important than any other neighborhoods in our city, and citizens who live there absolutely deserve access to a quality grocery store.”

He even pointed to a recent success story in another impoverished, majority African American neighborhood as a model for success.

Sadly, that too would succumb to the realities of modern-day supermarket realities before too long, leaving another food desert in its wake.

Just before those Kroger locations closed, the Binghampton community was rejoicing about the long-awaited opening of its first full-service grocery store after a decade-long search.

The Save A Lot supermarket was the anchor tenant in a brand new development at the prominent corner of Tillman and Sam Cooper Blvd. and a success story for the neighborhood and the Binghampton Development Corporation.

It ended Binghampton’s longtime status as a food desert and was hailed as a success across the board.

But the good times didn’t last long.

Sadly, just a few years after it opened, the building that housed the grocery store is empty once again. The cause was reportedly a nationwide restructuring of the Save A Lot company, but the subsequent difficulties in finding a replacement store showcase just how difficult the task can be to service this community with another supermarket.

The Binghampton Development Corporation and its team entertained 25 potential prospects, went into actual negotiations with several grocers, but ultimately an agreement that worked for all parties could not be reached. Real estate expert Shawn Massey with the Shopping Center Group pointed out two big challenges the community faced when trying to fill the supermarket vacancy. Speaking to the Daily Memphian, Massey noted that the first issue was shrinkage. The average grocery store operates on a 1-2% margin, he said. Additionally, the recent labor shortage due to COVID-19 meant that there was a fear of not finding enough workers to fill the jobs at any new store.

Essentially, he concluded that food store companies believe there’s a greater risk of opening a store in a community like Binghampton compared to a suburban community like Collierville or Germantown. Opening in one of those areas looks like a safer option to the business due to higher household incomes there, as well as the safety perception between the two areas.

So, the community is once again labeled as a food desert, with their closest grocery store located more than a mile and a half away and a 30-minute walk for many of the area residents without reliable transportation.

HOW CAN WE FIX IT?

There is no easy fix for the issue of food deserts in Memphis or in cities across America.

A number of creative approaches to help increase the ability of minority communities to obtain fresh, affordable and healthy food have been developed. But many of them offer only a temporary or surface-level fix, while the underlying issues of structural racism that discourage investment in and the serving of minority communities persist.

To really solve the food desert problem, it will take change from a number of different avenues. Challenges to resident segregation, commercial redlining practices and government policies that perpetuate the disparities in food access to low-income, minority neighborhoods all must be considered. Outside the box funding and policy ideas on a national level can help usher in generational change.

Food insecurity in itself is complex, but importantly, when food insecurity exists, it is both a symptom and consequence of the absence of upstream social protections," said Dr. Leanne De Souza-Kenney, the University of Memphis visiting Fulbright Canada Research Chair of Race & Health Policy. "Currently, solutions that occur in response to food insecurity are temporary and limited such as farmers markets and food banks.

These solutions are necessary, but must be recognized as short-term, seasonal and not designed to eradicate the source of the problem. In contrast, ‘upstream’ solutions that are sustainable will ensure education, living wages, a built environment that supports infrastructure for transportation to grocers and a cultural paradigm shift to truly believe that a society is only as healthy and prosperous as its most vulnerable groups.

An Unexpected Tool – Antitrust Law

Antitrust regulatory tools are probably not the first thing that comes to mind when thinking of ways to help address the food desert crisis across the country. However, some legal scholars have begun to re-examine our country’s food desert situation as a failure of the free market, which traditional antitrust laws are intended to protect.

This may in fact be one of a number of new tools in the fight for food desert elimination, especially on the supply side of the problem.

One notable antitrust scholar, UC Irvine Law School professor Christopher Leslie, believes that once food deserts are more widely seen as a failure of the competitive market, it will follow that the government should employ antitrust law and policy to help remedy the problem of food deserts in communities.

In a recent talk at the Yale Law School Big Ag & Antitrust Conference, professor Leslie notes that what he calls “scorched earth” policies are an issue where antitrust law enforcement could have a big impact on the elimination of food deserts.

“Many food deserts are the result of a premeditated strategy by supermarket chains to deprive certain neighborhoods of grocery stores,” said Leslie.

He notes that there are two main types of covenants involving grocery stores and their landlords or shopping center owners. One is commonplace and involves a grocery store negotiating leases with commercial landlords and demanding an “exclusivity covenant,” which prevents the landlord from opening another grocery store in the same complex. The second type of covenant is one he believes deserves much more attention, especially from an antitrust perspective with the goal of helping eliminate food deserts.

“Lack of space is the critical barrier to entry for supermarkets in cities,” he said. “One major reason that appropriate space is unavailable is that major supermarket chains use restrictive covenants that forbid their sold property from being used as a grocery store for decades to come.”

He has dubbed these “scorched earth” covenants and believes that they have created and preserved food deserts across the country.

These "scorched earth" covenants are put in place by grocery stores in order to prevent competition for their other stores that are in driving distance of the closed location. The big problem with this is that they are viewed through the lens of the ability of all citizens and customers to drive or have access to reliable transportation. The "scorched earth" policies work to push area residents into driving to supermarket’s other, often suburban- located, stores.

But they fail to take into account the many residents without cars or access to transportation. These residents are then left with no way to easily access fresh and healthy foods. A food desert is created as a result, especially in many of these urban areas with highly impoverished minority populations.

Another grocery industry practice that perpetuates food deserts is known as “going dark.” It refers to a situation where a grocery store in a shopping center closes but keeps on paying rent to the landowner in order to abuse their exclusivity contracts prohibiting the landlord from opening up another grocery store in their complex. Again, the intent by the grocery store is to eliminate competition and force customers to visit their other stores, while all too often creating a food desert in their wake.

Professor Leslie argues that both "scorched earth" covenants and the practice of “going dark” should be viewed as standard anticompetitive tactics that restrain free trade. The problem, he stated, is that these sorts of claims have not succeeded, due in large part to judges typically defining relevant geographic markets incorrectly.

“When analyzing antitrust claims against supermarket restrictive covenants, courts treat the relevant geographic market as the metropolitan area, meaning the entire city and surrounding suburbs,” noted professor Leslie. “For over 60 years, courts have been reluctant to define geographic markets as narrowly as neighborhoods, because judges assume that all consumers have cars.”

As is surely clear by this point, this definition does not take into account the reality for many residents in inner-city neighborhoods or poverty- stricken communities that food deserts are prevalently located. Professor Leslie recommends that courts begin to allow the definition of food deserts to inform how they define the relevant geographic markets in an antitrust case. Doing so would create more opportunities for new grocery stores to open up in underserved markets and potentially help eliminate food deserts.

He also suggests that antitrust regulators should take aim at these restrictive “scorched earth” covenants to help encourage supermarkets to re-enter a market.

By using antitrust regulation to remove some of the restrictive barriers and harmful practices utilized by major supermarket chains, could supermarkets have an easier road of entry into underserved markets?

It’s an interesting tool in the toolbox.

Increased Opportunities for Minority Investment

Another avenue of improvement deals with the failure of lenders and retailers to invest in businesses in low-income communities of color.

There are several efforts that have been carried out across the country in recent years to attempt to dismantle some of the elements of structural barriers to investment in communities with food deserts.

Pennsylvania established the Fresh Food Financing Initiative (FFFI), a statewide financing program designed to attract supermarkets and grocery stores to underserved urban and rural communities. It is a public/private partnership that provides grants of up to $250,000 and loans ranging from $25,000 to $7.5 million for the costs associated with predevelopment.

This includes costs like land purchasing and financing, equipment financing, capital grants for project funding gaps, construction finance and workforce development. Over the course of a decade, the program provided funding for 88 fresh-food retail projects in Philadelphia.

Former President Obama established the Healthy Food Financing Initiative during his presidency. It is a partnership between the Departments of Treasury, Agriculture and Health and Human Services, which allocates $400 million to rid the nation of food deserts by bringing grocery stores offering fresh fruits and vegetables and other healthy choices to underserved communities. It also aims to create and preserve quality jobs and to revitalize low-income neighborhoods by building a more equitable food system that supports the health and economic vibrancy of all citizens.

In 2021, at least $4 million was available for innovative food retail and food system enterprises that sought to improve access to healthy food in underserved areas. Grants ranged from $20,000 to $200,000.

Some Success in Memphis

For all of the struggles Memphis faces in regard to food deserts, there are a few glimmers of success in recent years, thanks in part to more economic development funding and incentives from city leaders.

After the Kroger in Orange Mound closed in 2018, residents were obviously distraught about their food situation. For more than a year, area residents waited for a new grocery store to open in the area. Finally, in December 2019, Superlo Foods opened in the former Kroger location, with vital assistance from the Economic Development Growth Engine (EDGE), the official economic development agency for the City of Memphis and Shelby County Government. EDGE gave Superlo a loan to operate in the former location in Orange Mound as part of the funding arrangement.

“Neighborhoods need good food choices,” said Reid Dulberger, president and CEO of EDGE. “Full service grocery stores are critical to the quality of life and the health of these neighborhoods.”

Dulberger said an EDGE committee signed off on giving Superlo a $100,000 loan, along with the $100,000 they received from the City of Memphis.

In addition to the help from EDGE, Kroger itself was vital in the entire operation coming to fruition. Kroger donated their building to Superlo, a property valued at over $500,000. Statistics from EDGE show nearly 100,000 people live within a 3-mile radius of the new store with a median household income of a little more than $31,000, and the federal government considers the spot severely distressed.

With the assistance of several different entities, and a bit of luck, these area residents once again have access to fresh food and an opportunity at a healthier life as a result.

The other major Kroger closure in Memphis in 2018 also hit an impoverished community extremely hard, but once again Memphis has seen some good luck come in when it was needed most.

Several months after the Kroger in South Memphis closed, local grocery chain Cash Saver opened in the same Southgate Shopping Center and has been successful in the years since.

Cash Saver did extensive research into whether their store could be profitable in the area. That research examined the number of homes, age ranges of residents and the median income of those in the area. The Cash Saver team also examined Kroger’s profit margins and they felt confident that they could improve upon them.

Again, the entity that came in to provide the vital assistance needed to put the project over the finish line was EDGE, which provided much needed financial incentives that helped lower Cash Saver’s risk in opening the new store.

But despite the stores’ individual success, South Memphis leaders are adamant that the root causes of food deserts in Memphis must be addressed before any long-term change can happen. They point to neighborhood revitalization as one of the key issues at play.

“If we don’t build the housing we need, we’re not going to get grocery stores, because they’re not willing to afford to be there,” said Rashun Austin, president and CEO of The Works, Inc., a nonprofit community development corporation serving South Memphis. “They already have these thin margins. Whether they can afford it or not, we can pretend that private businesses are charitable, but that’s not how capitalism works.”

Those larger issues are the harder hurdle to overcome.

Ultimately, we come to something like a giant circle. Poverty begets poverty. Systemic problems contribute to poverty; poverty contributes to food insecurity; food insecurity to health and education struggles; health and education struggles to employment struggles; employment struggles to poverty.

It is imperative to recognize that individuals are not necessarily at fault for falling into or getting trapped in the cycle of poverty, but that their situation may be a product of failures within larger systems.

It’s clear to see that there is not one answer to solving America’s food desert problem. But with more awareness of the problems and issues behind the root causes of food deserts, cities across the country may be able to plant the seeds of healthier communities going forward.