Marginal Decoration, Graffiti and Popular Religious Practices

A confusing patchwork of inscriptions blankets every surface of the Hypostyle Hall, especially on most of the 134 columns. Responsibility for the density of this embellishment lies not just with the Hall’s builders, Seti I and Ramesses II, but with a number of their successors. Disregarding the balance between inscribed and blank surfaces which would allow inscriptions to be seen to advantage, Ramesses IV, Ramesses VI and the High Priest of Amun Herihor filled empty spaces on columns, walls, and gateways with new texts. They applied bandeau texts listing strings of their royal titles and formulaic dedication texts on gateways and at the base of the walls. Ramesses IV systematically embellished large portions of most of the 134 columns with bandeau texts and friezes of his royal cartouches, all repeated endlessly. Indeed, his cartouche names appear literally thousands of times!

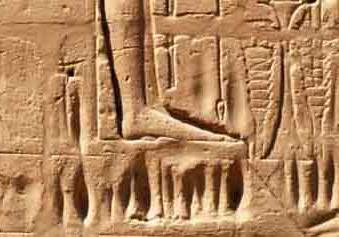

Examples of the large cartouches and Horus names added by Ramesses IV to the decoration

at the base of the large columns, showing later usurpation of Ramesses VI.

Example of a column with a row of cartouches at the top and a part of an offering scene, both parts of the decorative program of Ramesses IV in the Hall.

The Ancient Egyptian practice of adding new inscriptions to older buildings, even at the cost of erasing the name of the original builder, is strange to modern viewers who are likely to accuse the offending pharaoh of theft. Imagine if a modern American president tried to add his name to the Washington Monument or replace Lincoln’s statue with his own in the Lincoln Memorial. The public would be outraged! But such practices were considered perfectly legitimate, even normal, in Egyptian antiquity. Egyptians added new inscriptions to existing monuments for a variety of reasons. As with most of Ramesses IV’s inscriptions, a king might do so without actually removing the name of his predecessors.

Midway through his 67 year reign, Ramesses II added hundreds of new inscriptions to

the columns and nave of the Hypostyle Hall, sometimes erasing the names of his long-deceased

father Sety I in the process. Yet Ramesses acted not out of spite or hatred of his

father, but in celebration of his own great series of jubilee festivals. His successors,

including Ramesses IV and the High Priest of Amun-Re Herihor, added marginal inscriptions

on undecorated parts of the columns, seeking to associate themselves with their illustrious

predecessors Sety I and Ramesses II, but without erasing their names. In some cases,

however, Ramesses VI reinscribed Ramesses IV’s cartouche names with his own, but more

often, he left them untouched.

Even the common people of Egypt left their mark on this great monument. They scratched

images of the gods on the Hypostyle Hall’s exterior walls and gateways. Along with

the “official” icons of the gods carved by the pharaohs’ artists, pious visitors sometimes

carved their own private ex voto images of gods and sacred objects, and these often became objects of worship by religious

pilgrims. Most visitors were rarely permitted entry into the Hypostyle Hall and not

at all to the inner sanctum, yet they could approach the outer walls, courtyards,

and gateways to express their devotion to the gods within.

Another common manifestation of their piety are countless rows of vertical oval grooves

carved on the walls and columns (as shown in the image to the right), which testify

to the popular magical practice of tapping the shrine’s power by scraping off bits

of stone for personal use. To protect the icons carved on the outer walls and gateways

from over-zealous pilgrims, temple priests ordered protective veils attached to the

walls to screen holy images from view. These veils consisted of wood panels or perhaps

cloth screens mounted on wooden frames. The veils have long since disappeared, but

sets of holes drilled into the walls that encompass certain divine images indicate

where these screens were once erected against the temple’s walls. It is possible that

veiled icons were occasionally revealed to pilgrims on certain holy days. On the north

wall of the Hypostyle Hall, Pharaoh Ramesses III erected a more elaborate lean-to

shrine to envelop an image of the Theban Triad once these icons had developed a special

cult following among pious visitors.

Another common manifestation of their piety are countless rows of vertical oval grooves

carved on the walls and columns (as shown in the image to the right), which testify

to the popular magical practice of tapping the shrine’s power by scraping off bits

of stone for personal use. To protect the icons carved on the outer walls and gateways

from over-zealous pilgrims, temple priests ordered protective veils attached to the

walls to screen holy images from view. These veils consisted of wood panels or perhaps

cloth screens mounted on wooden frames. The veils have long since disappeared, but

sets of holes drilled into the walls that encompass certain divine images indicate

where these screens were once erected against the temple’s walls. It is possible that

veiled icons were occasionally revealed to pilgrims on certain holy days. On the north

wall of the Hypostyle Hall, Pharaoh Ramesses III erected a more elaborate lean-to

shrine to envelop an image of the Theban Triad once these icons had developed a special

cult following among pious visitors.