Hypostyle

The Karnak Hypostyle Hall Project: Preliminary Report (Seasons 1992-2002)1

By: William J. Murnane,† Peter J. Brand, Janusz Karkowski & Richard Jaeschke

1.0 History and Program of the Karnak Hypostyle Hall Project

1.1 Introduction

The Great Hypostyle Hall in the Temple of Amen-Re at Karnak, although it is well known to everyone who visits Luxor, is still poorly documented for Egyptologists. Extensive general discussions in the earlier literature2 remain, for all their virtues, incomplete, and the same can be said for a number of useful essays that have focused either on features within the Hall3 or on broad questions of its decoration.4 Indeed, the lack of basic documentation has been at the heart of more than a few controversies that only drive home how fragile our understanding of this building really is.5

1.2 Origins of the Hypostyle Hall Project

The first systematic attempt to record the Great Hypostyle Hall began during the late 1930s with Harold Hayden Nelson. As the founding Field Director of the Epigraphic Survey of the University of Chicago's Oriental Institute in Luxor ("Chicago House"), Nelson was acutely aware of the gap that still separates excavation from proper publication. Perhaps his most enduring contribution to the ongoing process of recording the monuments at Thebes is a system he developed to identify discrete scenes and elements of decoration, assigning them numbers so that they could be referred to easily.6 In time, even though the Epigraphic Survey under Nelson was fully occupied with recording the mortuary temple of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu, the Great Hypostyle Hall at Karnak gnawed at Nelson's professional conscience to such an extent that he undertook to record it himself in his spare time. Drawings of most of the scenes on the interior walls were ready by the early 1950s, along with a manuscript (now lost) of translations – but the book was not accepted for publication at Chicago. Part of the problem, undoubtedly, was that Nelson had felt obliged to execute the drawings himself, in a manner vastly simpler and on a much smaller scale than the facsimile copies that were being produced by the Epigraphic Survey at the time. The material thus remained unpublished when Nelson died in 1954,7 and it continued to languish in the Research Archives of the Oriental Institute until William J. Murnane sought it out in the mid-1970s. By then, since it was clear that no scholarly organization would soon undertake to record the Great Hypostyle Hall properly, the case for issuing Nelson's drawings as a stopgap service to the profession seemed compelling. These, after being checked in the field for substantive accuracy, were finally issued at the beginning of the 1980s,8 while further work was undertaken to complete the project he had begun. A proposal by Vincent Rondot to record the architraves was accepted;9 and this writer began to document not only the "stereotyped" decoration on the columns (i.e., everything but the scenes) but also the many blocks that had tumbled from the tops of the building's walls and were kept, in haphazard fashion, on the grounds of the Temple of Amen. By the mid-1980s, however, the press of other work,10 followed by the transfer of Murnane's professional life from Egypt to the U.S.A., forced the project's suspension until 1990, when it was started afresh under the sponsorship of The University of Memphis, in cooperation with the Franco-Egyptian Center at Karnak. Since then the documentation of the Great Hypostyle Hall at Karnak has been proceeding as follows, with results to be published in the following tentative sequence:

Nelson's drawing of the reliefs on the inner walls of the Hall, already published, will be supplemented with a detailed commentary on the scenes themselves.11 This discussion will cover the style(s) of carving, alterations, physical condition, traces of paint, and similar epigraphic commentary, along with translations of the texts and a provisional analysis of the decorative program of the Hall as seen on its standing walls.12 Moreover, in order to illustrate stylistic and palaeographic details that cannot be seen from Nelson's drawings, this volume will be extensively illustrated with photographs drawn from the archives of the Chicago Epigraphic Survey and the Franco-Egyptian Center at Karnak.

1.3 Program of Epigraphic Work

The passages and doorways on the north,13 south and west sides, and at the southeast corner of the Hall, since they are mostly excluded from earlier publications, are to have a volume of their own (A, C, E, F & H). Field work on these walls is essentially finished, and the drawings only await final inking before they will be ready for publication (see below 4.1).

The architraves undertaken during the early 1980s as a personal project by Rondot, formerly of the Franco-Egyptian Center, are now published.14

Murnane has recorded the "stereotyped" inscriptions on the shafts of the columns and the original bases that survive (Figs. 12A-B & 65). Preparation of the manuscript, which will include a description of the color that remains on the columns, is in progress(see below 4.4).

The war scenes of Seti I on the north exterior wall have been recorded by the Chicago Epigraphic Survey (Fig. 6).15 This expedition is currently engaged in recording the complementary war scenes of Ramesses II on the south outer wall (see below 4.2).

|

Fig. 6: Battle scene from the south exterior wall. |

Blocks fallen from the tops of the standing walls of the Great Hypostyle Hall are stored throughout Amen's precinct at Karnak. Murnane made initial use of this material while working on the Chicago Epigraphic Survey's publication of Seti I's war reliefs and was able to reconstruct the overall outlines of the decoration on the missing upper reaches of the Hall's north outer wall. By the time he left Egypt in the mid-1980s he had also noted the positions of over one hundred blocks from the Hall's interior. A number of these fragments have already been reassembled into a scene that must have stood originally in the fourth register of the west wall's southern wing (Fig. 2).16

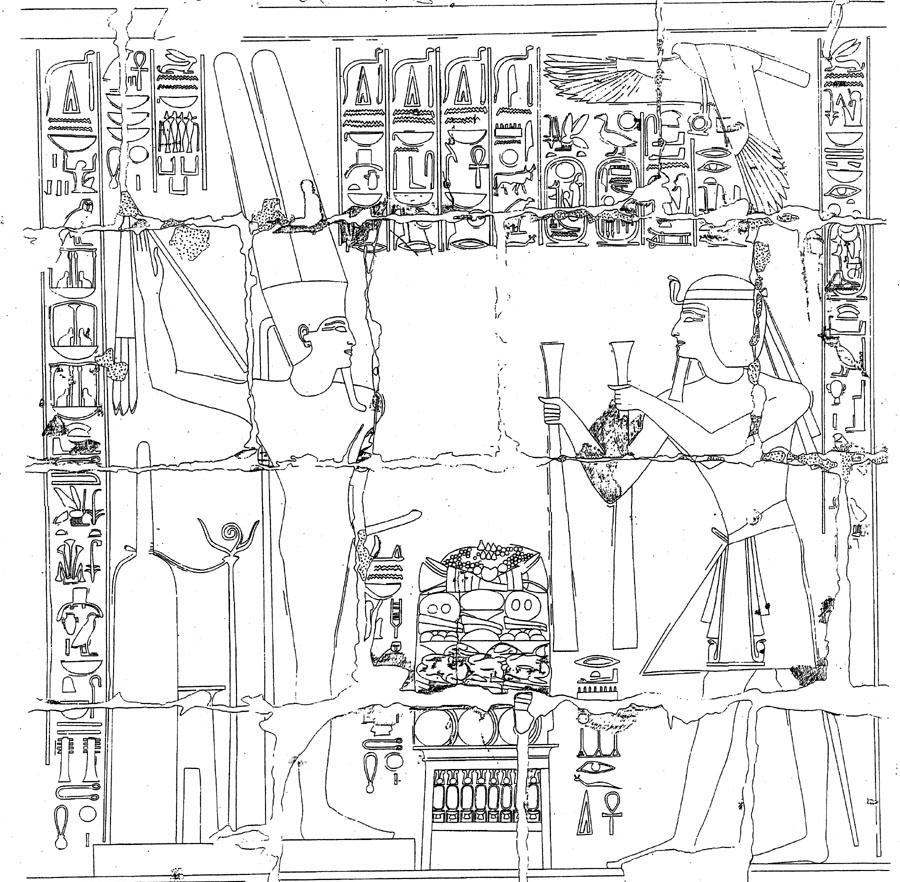

|

Fig. 2: Scene reconstructed from loose blocks. |

There is every reason to think, therefore, that similar results could be obtained with blocks from other, more seriously damaged walls of the building.17 In recent years many of the fragments have been moved onto waterproof platforms, as well, where they are safe from further deterioration that results from being in direct contact with the ground and its salt-inducing moisture (Fig. 3).18 The Supreme Council of Antiquities and the Franco-Egyptian Center have recently agreed to clear the last important sector where blocks from the Hall are to be found, on the hill that lies east of the path which leads from the Hall's northern doorway to the Temple of Ptah.

|

Fig. 3: Block from reconstructed scene on waterproof platform. |

The University of Memphis began working on these, as well as other fragments that lie around the site, in the spring of 2000 and 2002 (Fig. 4). The scenes that emerge from the joining of these fragments will be drawn and collated,19 but the photographed assemblages of the blocks will also be integrated into photographic composites of the Hall's inner walls that the Franco-Egyptian Center is now preparing. This reintegration will serve as a guide to future restorers, when and if it is decided to put these reassembled scenes back onto the walls of the Great Hypostyle Hall (see below 2.7 and 4.3).

|

Fig. 4: Janusz Karkowski measuring a block from the south wing of the Hall, 2001 season. |

The scenes on the columns are still to be recorded in detail (including those that are now lying in fragments north of the Hall, two of which have been reconstituted, on paper, by Murnane). Most columns have only one scene, executed originally by Seti I (in the northern half) or Ramesses II (southern half), but columns adjoining the central aisle each have two such scenes. Ramesses IV later filled the empty spaces on all of the columns except those in the Hall's south-western quarter, generally adding two scenes per column.20 Most of these 346 scenes survive (excepting those on the badly damaged columns at the southeast corner of the Hall's northern half), and although most of them are not executed on the large scale found on the colossal open-papyrus columns in the central aisle (Cols. 1-12), the prospect of recording them all poses a daunting logistical challenge. Advances in computer-aided techniques for handling such images, along with financial issues, will have to be considered before a final decision is made on the manner in which the columns will be recorded (see below 4.4).

Finally, due to the rapid deterioration of some of the interior wall scenes– scattered throughout the building– a program of "salvage epigraphy" was undertaken in 2001 to record those scenes in the most immediate jeopardy of decay (Fig. 5.).

|

Fig. 5A: Ramesses offering cloth, west wall, south half, bottom register. Note area in front of the king's forward leg as it appeared in 1995. |

|

Fig. 5B: Same scene in 2001 after salt infiltration damaged the text in front of the king's leg (left). Fig. 5C: Detail of same inscription in 2001 (right). |

This represents only the first step in the process of eventually re-recording all of the interior wall scenes published by Nelson. Given the amount of unrecorded material in the Hall, this cannot be the first priority, except for the most endangered reliefs. Neither can the drawings of Nelson, however, stand as the definitive publication of the interior wall scenes, even when augmented by the forthcoming volume of translations and epigraphic commentary. For this reason, we have begun to redraw selected wall scenes that are in danger of immediate deterioration as part of our "salvage epigraphy" program (see below 2.8-2.9.1).

The laborious program of recording described above will lead, undoubtedly, to an accumulation of valuable details on the history of the Great Hypostyle Hall. Ideally, however, and especially when enhanced by the addition of the fragments from the tops of the standing walls, it should also lead to a "grammar" of decorative and religious themes inside the Hall. These findings might then be applied to other, more incomplete buildings of the New Kingdom. The system used in decorating the Great Hypostyle Hall may thus shed light on the mentality that underlies this and other great religious buildings that survive from ancient Egypt.

2.0 SUMMARY OF FIELD SEASONS BETWEEN 1992 AND 2002

What follows is a brief description of our fieldwork in the twelve years since the Karnak Great Hypostyle Hall Project of The University of Memphis began. We will confine ourselves here largely to a description of the field work and some of our preliminary findings. More detailed interpretations and epigraphic/historical findings are given in a later section of the present report.

2.1 1992 FIELD SEASON

The Hypostyle Hall Project's first two field seasons of May-June 1992 were devoted to photography of reliefs to be recorded in facsimile during the coming year.21 Reliefs in the eastern passageway through the Second Pylon22 were photographed with the aid of a six story scaffolding generously lent to us by Chicago House (Fig. 1A).23 Another early focus of our work was the battle reliefs of Ramesses II on the south exterior wall, (Fig. 1B), and a handful of miscellaneous ritual tableaux from the north, south and south-east gateways (Fig. 1 E-F).24 Edward Bleiberg also mapped the locations of previously identified fragments belonging to the Hall scattered in the block yard south of the temple proper.

|

Fig. 1: Plan of Hypostyle. Locations marked with letters indicate areas where the project has worked since 1992. |

2.2 1993 FIELD SEASON

Our third summer field season worked at Karnak lasted from May 16 until June 19, 1993. The project staff25 worked on three distinct phases of the program, to wit:

(1) The photographer completed the recording of surfaces left undocumented at the end of the 1992 season -- i.e., reliefs on the southeast exterior corner of the Hall,26 the exterior jambs and thickness of the south gateway,27 and the thickness of the north doorway.28 Additional photographs of scenes from the western passage into the Hall (at the east end of the Second Pylon) were also taken.

(2) Fourteen block fragments which can be joined to form substantial parts of scenes from inside the Hall and had been identified by the field director in the early 1980s, were re-located and traced, and these tracings photographed. These were later reconstituted on paper, giving further impetus to the location and joining of further fragments which continued during later seasons.29

(3) Fifteen photographic enlargements of scenes within the western passage of the Second Pylon at the entrance into the Hypostyle Hall were penciled in and given a preliminary collation (Fig. 7).

|

Fig. 7: Barque scene from west passage, south wall, bottom register. |

Work on the remaining three scenes in the passage (bottom registers, both sides)30 was deferred until the 1994 season, when drawings were made on new enlargements at a larger scale in order to do greater justice to the complex decoration found in these portions of the reliefs. Happily, enough had been done already to verify Murnane's initial hypothesis regarding these reliefs, which was that in their present form they are Ptolemaic re-editions of nearly identical scenes carved during the Nineteenth Dynasty. Not only did we find substantial traces of the earlier reliefs, which confirmed their basic similarity to the present Ptolemaic scenes; but a surprising amount of original Ramesside decoration was found to have been reworked, with varying degrees of thoroughness, or even incorporated in its original form, when these walls were recarved in the first part of the second century B.C., more than a thousand years after they were first inscribed (Fig. 8).

|

Fig. 8: Ramesside hieroglyphs reworked into Ptolemaic reliefs from the western passageway. |

Moreover, we were also able to confirm that the sunk relief cartouches of Ramesses II, for all their "Ptolemaic" appearance, were indeed based on that king's original usurpation of the raised relief cartouches of one of his immediate predecessors in these scenes (Fig. 9).Even when the signs in these cartouches had been retouched by the Ptolemies' sculptors-- so that their paleography was in line with contemporary taste-- evidence of Ramesses II's original carving still survived in many places. Even better, distinct traces remained of the original raised relief hieroglyphs which Ramesses II had shaved down when he usurped these cartouches -- and these belong, not to his father, Seti I (as scholars had long assumed)31 but to Ramesses I, his grandfather (Fig. 10).32 The implications of this data for the building history of the Great Hypostyle Hall at Karnak would be further explored during subsequent seasons and are discussed below.

|

Fig. 9: Cartouche of Ramesses II usurpedfrom Ramesses I in the western passage (left). Fig. 10: Drawing of the same cartouche (right). |

2.3 1994 FIELD SEASON

The Karnak Hypostyle Hall Project worked at Karnak from late May until the end of June, 1994.33 Initial tracings of the remaining reliefs in the Second Pylon passageway were completed and first collation of drawings made in the previous season was continued. Elsewhere in the Hypostyle Hall, initial drawings were also made of selected reliefs from the north gateway34 and the thickness of the south-east gateway (Fig. 11).35

|

Fig. 11: Ramesses II censes Amen-Re and Mut. Scene from south-east gateway, south wall. |

The narrow confines of the south-east passage made accurate photography impossible, and so direct, one to one scale tracings on clear plastic were made instead. These tracings were later photographed and the photos used to make collation blueprints. At the same time, William Murnane's ongoing examination and recording of the stereotyped decoration on the columns inside the Hall and the search for "new" fragments from its upper registers in the block yards around Karnak, continued apace. Of particular significance was his effort to disentangle the three versions of the cartouches of Ramesses IV/VI on the bases of the twelve great columns of the central nave, and some of the best preserved examples were traced on plastic sheets (Fig. 12). The curved surfaces of the column drums, which also narrow slightly at a curve at their bases, made our normal method of drawings based on photographs impossible.

|

Fig. 12A: Cartouche of Ramesses IV usurped first by himself and subsequently by Ramesses VI, from the base of column 8 (left). Fig. 12B: Facsimile drawing of the same cartouche (right). |

2.4 1995 FIELD SEASON

1995 was the Hypostyle Hall Project's first long season, extending from late January through early May.36 The beginning of the season was spent in Cairo, expediting the importation into Egypt of an aluminum scaffold to replace similar equipment generously loaned to the expedition by the University of Chicago's Epigraphic Survey (at Chicago House) during the previous three seasons. The new scaffolding was imported from England and was donated to the S.C.A. with the understanding that it would be stored in Luxor and made available henceforward, on timely notice, for the expedition's use during all subsequent field seasons. The equipment was successfully collected at Cairo Airport on 30 January and immediately dispatched by truck to Luxor, where it arrived 1 February. It was then transferred to the S.C.A. storerooms at Karnak on 2 February, and released a few days later into Karnak Temple for the expedition's use during the 1995 season. As stipulated in the arrangement with the S.C.A., the equipment was returned to the magazine outside Karnak Temple at the conclusion of the season, on 8 May 1995.

During the 1995 season, the second major phase of the project was begun when initial drawings of the battle reliefs of Ramesses II on the south exterior wall of the Hypostyle Hall were traced on photographic enlargements (Fig. 13).37

|

Fig. 13: Scaffolding on south exterior wall, 1995 season. |

These included the ritual scenes on the exterior jambs and outer thicknesses of the south portal.38 The process of first collation of the Second Pylon reliefs was now largely completed-- save only for final "spot checks" in the 1997 and 1999 seasons-- along with drawings from the north and south-east gateways. Murnane had earlier identified a ritual scene of Ramesses II from loose blocks lying in the south block yard at Karnak. The original provenance of this tableau, which depicts Ramesses in the presence of Horus, Seth and two goddesses was determined to have been the top of the southern half of the west wall adjoining a huge scene of Ramesses II. Drawings of the individual blocks were now fully collated and a drawing of the reconstructed scene was made on paper from these corrections.39

In 1995, William Murnane made some final refinements in his record of the stereotyped decoration of the columns, which he had begun in the 1970s and had augmented during practically every season of the Hypostyle Hall Project since 1992. The work in 1995 concentrated on completing the record of reworked cartouches at the bottoms of the columns, which occurs on three-quarters of the columns inside the Hall, where Ramesses IV had added a cartouche frieze on the "leaves" carved around the bases. In many cases these names were altered, in the first place by Ramesses IV himself (who modified the spelling to make the divine figures larger) and later by Ramesses VI, who usurped them. The manner in which these alterations were done was checked this season in greater detail than before and copious notes taken, so that this data could be included in the final publication of the column decoration.

2.5 1997 FIELD SEASON

Our 1997 field season, which lasted from mid May through late June, was devoted exclusively to collation work.40 Final checks of corrected drawings of the Second Pylon and south-east passageway reliefs were completed, as well as a number of discrepancies and uncertainties which arose as the original drawings were corrected against the collations sheets and photographs of the reliefs in question that had been made between field seasons in 1994-1996 by the artist and reviewed by the Project Director. Such minor conflicts and questions are inevitable despite the best efforts of the epigraphers in the field, justifying the epigrapher's adage that "many sets of hands and eyes checking many times ensures the most accurate and objective facsimile of reliefs humanly possible."

Initial collation of scenes on the exterior and thicknesses of the south gateway also commenced in 1997. Although the decorative scheme of the portal is seemingly banal, consisting wholly of "generic" offering scenes and bandeaux texts, it did present us with a number of epigraphic challenges and even a few historical findings (Fig. 1H). Much of the relief is in poor condition, like the rest of the south wall, having suffered considerable wind erosion and exfoliation of the surface (Fig. 14-15).

|

Fig.14: Ramesses II offers to Amen-Re and Mut. South gate scene, exterior west jamb, middle. The scene was originally carved by Ramesses in the name of Seti I, but later changed to his own name. |

|

Fig. 15: [King] offers to [deity]. South gate, exterior lintel, west end. Preliminary drawing. |

In addition, the faces and most of the limbs of the king and gods on the upper register and lintel of the south gate have been hacked out by vandals in the Middle Ages. Sadly, most all of the faces of the gods on the middle register of the jambs of the south gate are missing along with several patch stones on which they were inscribed. Remaining traces, e.g., the chin of a goddess on the east jamb, indicate that this register was not defaced. Superstitious defacement of reliefs is quite common at Karnak, and we had already encountered it in the eastern passageway of the Second Pylon where we found that it was often possible to recover substantial traces of the profile and other details of hacked out heads. Exfoliation of the already hacked surfaces made this task all the more difficult on the south gate, however, and as a result we were generally only able to recover partial outlines.

An unexpected result of our collation of the south gateway was the discovery that reliefs on the middle register of the jambs and door reveals were originally inscribed for Seti I, although the rest were carved for Ramesses II (Fig. 16). The south gate had first been inscribed in raised relief in the name of Ramesses II, who later converted this decoration to sunk relief as he did with other raised relief in the southern part of the Hypostyle Hall.41 Apparently he made a small homage to his deceased father by having a fraction of the gateway reliefs carved in Seti's name, but his filial piety extended through his conversion of the raised relief to sunk. Later in his reign, however, he replaced these sunk relief cartouches of Seti I with his own. The same phenomenon has long been known from two reliefs on the bottom jambs of the interior face of this same gateway where, Seti I appears not as the officiant, however, but as a deified king and secondary recipient of his son's offerings to Amen-Re.42

|

Fig. 16: Drawing of the usurped cartouche from the south gate, middle register. Seti I! Ramesses II. |

A closer parallel to the "new" reliefs on the middle register of the exterior of the south gate is found in similar scenes on the jambs of the west gate of the Hypostyle Hall, where the four registers alternate the cartouches of Seti I and Ramesses I throughout the eight scenes (Fig. 17).43

|

Fig. 17: Ramesses II (originally Ramesses I) offers nw-jars. West gateway, north jamb, top register. The scene was carved by Seti I in the name of his deceased father. |

2.6 1999 FIELD SEASON

In the spring of 1995 the expedition made preliminary copies of Ramesses II's battle scenes on the south exterior wall, including the southern doorway of the Great Hypostyle Hall.44 The doorway scenes were collated during a short field season in 1997, but it was only during the May-June 1999 field season45 that some of the war scenes themselves were given their first collation; the focus of our work was on the scenes that lie east of the doorway, which had been documented in hand copies but never in line drawings.46 After a two year absence, this season brought home to us more than ever before the alarmingly rapid rate of decay that is overtaking the monuments. Even high up on the walls, we found yellow stains left by dissolved sandstone which had cascaded down the side of the south exterior wall with rainwater during a violent thunderstorm. The amount of precipitation in Upper Egypt has increased dramatically in the past decade with disastrous consequences for the standing monuments.

As our collation of the battle scenes on the east side of the south gateway continued, we found additional traces of the Battle of Kadesh palimpsest which had been overlooked by earlier scholars (Figs. 18-19).

|

Fig. 18: South exterior wall, large smiting scene, detail of palimpsest. In the midst of the king's leg, a palimpsest of the Hittite spies from the Kadesh narrative are beaten by three Egyptian soldiers. Below are the heads of a row of Egyptian soldiers. |

|

Fig. 19: South exterior wall palimpsest. Ramesses II leads prisoners to Amen with palimpsest of the Orontes river and an Egyptian soldier slaying a Hittite. |

These were often so faint that they were only detectible under the closest scrutiny at the wall. The erosions and exfoliation of the surfaces, coupled with the tendency of the ancient sculptors to rely on plaster to smooth poorly dressed stone, made our work all the more difficult. Large areas of intermittent "quarry hacking" and voids left by missing patching blocks also robbed us of much of the decorative scheme.

2.7 2000 FIELD SEASON

The Institute of Egyptian Art and Archaeology at the University of Memphis worked at Karnak from the middle of January until mid-May in 2000. Once again, this project was authorized by Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities and functioned with the cooperation of the Centre Franco-Egyptien pour l'Etude des Temples de Karnak.47 Since it had an unusually long working season in 2000, the Project was able to focus on a number of different areas.

2.7.1 Epigraphy (1): Reliefs of Ramesses II and Others on the Outer Walls

The project began its work by recording the three surviving registers of scenes, never before copied in their entirety, on the eastern face at the southeast corner of the Hall.48 This decoration, it must be admitted, consists for the most part of utterly stereotyped offering scenes (Fig. 1H). True, these do continue, to some extent, the martial themes that prevail around the corner: in counterpoint with the long scene devoted to the presentation of prisoners to the Theban Triad located above the "Battle of Kadesh" Poem on the south wall,49 we find – in the middle register of the east face – Ramesses II presenting captives and spoil to Amen, Mut and Khonsu (Fig. 20).

|

Fig. 20: Ramesses II leading prisoners and presenting spoil to Amen-Re. South-east gateway, preliminary drawing. |

Above and below, however, are the most conventional of offering scenes – but while those at the top of the wall are both incomplete and rather crudely carved, the scene in the lowest register, adjoining the doorway, has an unexpected interest. To begin with, it does not belong to Ramesses II at all, but dates to the reign of his remote descendant, Ramesses IX (Fig. 64).50

| Fig. 64: Ramesses IX receives live from Amen-Re. South-east corner, south end. |

The scene was thus a "filler," almost certainly carved at the same time that Ramesses IX built and decorated the adjacent gate at the north end of the court.51 That this space had been left unfilled by the great Ramesses II is not without interest – for a similar "blank" was also left on the cross-wall that extends from the south wall of the Great Hypostyle Hall,52 when Ramesses II erased his original wall reliefs for the battle of Kadesh, leaving only the bandeau text at the top of the wall (see below 4.2).

After finishing their work at the outer southeast corner of the Hall, the epigraphers turned their attention to the war scenes of Ramesses II on the outer southern wall, west of the cross-wall that constitutes the west side of the transverse axis at Karnak Temple (Figs.18-19, 21-24).53

|

Fig. 21: Smiting scene immediately west of the south gateway with palimpsest of Kadesh narrative. |

|

Fig. 22A: Palimpsest of an Egyptian soldier slaying a Hittite suppressed by the legs of an enthroned Amen-Re (left). Fig. 22B: Collation sketch of the same palimpsest (right). |

|

Fig. 23: Collation sketch of a name ring with palimpsest traces of the "Bulletin" text of the Battle of Kadesh. South exterior wall, western smiting scene (left). Fig. 24: Collation sketch of the god Sopdu from the south wall battle scenes with palimpsest of an Egyptian soldier's head from the Battle of Kadesh. South exterior wall, western smiting scene (right). |

These scenes, covering three registers at either side of the central doorway, are more completely preserved than Seti I's battle reliefs on the northern outer wall;54 missing are only the bulk of the small offering scenes that occupied the upper register, along with all of the other material (bandeaux, torus moldings and cornices) at the very top of the wall. Otherwise, though, Seti's war monuments offers a poor analogy to this one. For one thing, the three registers on the west side are much longer than those on the east, which are cut off by the southern cross-wall; Seti's reliefs, by contrast, occupy the full length of the northern wall on both sides of the central doorway. Moreover, while each register of Seti I's war monument is devoted to a separate campaign, the arrangement of Ramesses II's battle scenes is more cryptic.55 To begin with, none of them is dated, and each register lacks the regularity that is observed in Seti's sequences (in which the battles are invariably followed by the triumphal return to Egypt and presentation of the spoils at Karnak). In Ramesses' monument, by contrast, such an arrangement occurs in only one register; and while it might arguably appear under an abbreviated form in another, as well as in the three abbreviated eastern registers, it is entirely absent in the upper register on the western side.56 Most scenes show the king attacking one or more fortresses, either on foot or in his chariot – but, owing to the irregular arrangement, Ramesses II's scenes cannot be arranged as surely as can those of his father. Eventually, it may be possible to identify the locale of each battle by means of the names inscribed on the individual forts; but this will not be possible until all of these texts receive their final collation, and can next be equated with toponyms from Syria-Palestine.

The expedition had begun collating its preliminary drawings of these scenes, made in 1995, during its short season in the spring of 1999, and it was hoped that the balance of this material could be checked during the spring of 2000. This expectation proved over-ambitious: only a fraction of the remaining scenes were finished during the 2000 season, leaving the rest for the 2002 and beyond. Moreover, since the fall of 1994, when a series of torrential storms and flash floods struck the Luxor area, the progression of damage to monumental reliefs in the Luxor area has accelerated at an alarming rate. By 1999, when first collation of the battle scenes on the south wall began, recent decay of lowermost portions of the important topographical lists was sadly apparent.57 This damage continued to progress on the south exterior wall. The prime objective of the 2000 season was, therefore, to collate of the most endangered reliefs on the south exterior wall. These were confined to the lowermost register. Our scaffolding, which usually rises to six stories, was dismantled and converted to three smaller two story scaffolds. These were spread out along the bottom of the south wall in order to collate all of the most endangered reliefs, which was accomplished by the beginning of April.

Although this "salvage epigraphy" took us beyond the reliefs adjacent to the central doorway where traces of the erased Battle of Kadesh narrative are found, we were able at least to do some work on the palimpsest inscriptions we uncovered in 1995, as some of these are found on the lowermost register. Some of these palimpsests had already been noted, over ninety years ago, when it was first observed that the present battle scenes had been superimposed onto an erased version of the Battle of Kadesh.58 While the pictorial elements of that original version are clearly visible (Figs.18-19, 21-22), the texts that went with them have previously received more cursory treatment: earlier copies, based as they were on photographs alone, had noted only the most deeply cut of the hieroglyphs,59 and even in the late 1970s it could be asserted that the "total length of these original lines is uncertain."60 Both the dimensions of this composition and its identity became clear, however, as soon as it was closely examined for the first time, in 1995: it is the so-called "Bulletin" of the Battle of Kadesh, and the six fragmentary columns extant come from the second half of the text (Fig. 23). Despite its deplorable condition, enough is preserved of this version to show that it is somewhat different from the copies found at other localities,61 and it is already possible to fill some lacunae in passages left fragmentary in other copies. A fuller examination of the traces must wait until a later season – but even so, what has been noted to date is most promising, not only for an improved copy of the text itself, but in helping us toward a better understanding of how such "rhetorical history" was composed and modified at the various locations where it was "published" on temple walls.

2.7.2 Epigraphy (2): Fragments

In the mid-1980s, W. J. Murnane noted among the stone fragments that lay scattered around the grounds of the temple of Amen numerous blocks that seemed likely to have come from the Great Hypostyle Hall. In general, blocks in sunk relief had been deposited to the south of the main temple, while others in raised relief – clearly from the northern part of the building's interior (Figs. 3, 25-28) – had been stored to the north. H.H. Nelson had already reassembled a number of fragments and restored them to the upper register on the east side of the south wall, inside the Hall.62 Out of the fragments Murnane found, yet another scene had been pulled together and even located, at the top of the south wing of the Hall's western interior wall.63

| Fig. 25: Raised relief block of Seti I originally from the north wall of the Hypostyle Hall. |

|

Fig. 26: Sunk relief block of Ramesses II from the south wing of the Hall. |

|

Fig. 27: Raised relief block of Seti I from the north wing with traces of paint. |

|

Fig. 28: Block from the north gateway, interior lintel. Part of a scene showing the king running. |

More serious work with these fragments had to wait, however, until the spring of 2000, when the Project was joined by Janusz Karkowski (Fig. 4). Conditions at Karnak, as well, were now more favorable for this sort of work, since most fragments had been moved onto waterproof brick platforms, and it was now easier to examine these blocks than before, when they were chaotically disposed about the grounds. A fresh survey of the "block yards" around the temple of Amen turned up numerous new fragments – some of them identifiable as coming from specific localities inside the Hall. Some elements of the "lost" walls (i.e. the lintel belonging to the inside of the doorway at the north end of the wall) are already coming together (Fig. 28). Most of the more obvious "joins" have already been done, though, and it will take much more study of both the standing walls and the fragments before much further progress is made.

Using a large format camera, Karkowski compiled a photographic dossier on all the loose blocks that could be photographed at or near a right angle. Many blocks lying on the hill to the northeast of the Hypostyle Hall itself lay very close together making photography practical or impossible. Where possible, these were traced on clear plastic film. Still others will have to await consolidation and movement to waterproof platforms.

2.7.3 Conservation of Loose Blocks and Block Fragments

By Richard Jaeschke

While most of the stone fragments from the Hypostyle Hall have already been moved onto waterproof platforms, and are thus out of danger from further deterioration owing to the infiltration of moisture from the ground, one significant area remains untouched: this is what we have come to call "Ptah Hill," the rise that lies northeast of the Hall and to the east of the path that leads from the main temple of Amen to the temple of Ptah. This ancient mound was a convenient dumping-ground for blocks that Georges Legrain dragged out of the Hall, after substantial parts of it collapsed in the 1890s, and none of this material had been touched since his day (Fig. 29 & 31). The area remains covered by a confusing welter of architrave fragments, column drums, abaci and blocks from the walls of the Hall – many of these deteriorating, as they are split by the persistent action of the plant life around them (Fig. 30) or disintegrate through contact with the moist ground. Even directly to the north of the Hall, not a few blocks lie directly on the ground, and many of the surfaces remain filthy owing to their previous contact with the ground.

|

Fig. 29: Conservator Richard Jaeschke working with Hypostyle Hall blocks on "Ptah Hill" north of the Hall. |

|

Fig. 30: Split block with camel thorn grass growing in one of the cracks. |

|

Fig. 31: Removal of earth from a block lying on the ground. The lower part of the block is saturated with moisture and salts. Detached fragments have been conserved separately for re-attachment later. |

Although the Supreme Council of Antiquities has designated the blocks on "Ptah Hill" as urgent candidates for moving, logistical problems at Karnak prevented dozens of these blocks from being shifted. Thus it seemed advisable to bring out a conservator, in order to assess the condition of these blocks and perform such emergency conservation as seemed necessary before they can be moved to a safer and more permanent resting place. This was done in February-March 2000 by Richard Jaeschke.

Conservation work began on the blocks belonging to the interior walls for the Hypostyle Hall in Karnak on Saturday, February 26, 2000 and concluded Sunday, March 26, 2000. The first operation was to identify the blocks concerned. These lay, mixed at random with other blocks from different architectural locations, on "Ptah hill" between the Hypostyle Hall and the Ptah temple at the ancient mud brick boundary wall (Fig. 29). A few others were found to be on or near the mastabas just outside the Hypostyle Hall (Fig. 3).

When the blocks were first identified, a small area on each was coated with a viscous solution of Paraloid B72 acrylic resin (a copolymer of ethyl methacrylate and methyl acrylate) in acetone. As each block was individually identified, its number was marked on the acrylic resin patch using a permanent, lightfast, black marker pen and coated with a further layer of the acrylic resin. This resin protects the surface of the stone from being stained by the ink of the number and resists abrasion and other damage that could remove or obliterate the number. When the number needs to be removed in the future it can be cleaned off using swabs of acetone to dissolve the resin, without leaving any mark or stain on the stone.

Initially, 70 blocks were marked, then identified and an number assigned. Further blocks were discovered and identified later. Some blocks which had been given the initial resin patch were later found not to be relevant so a small "X" was marked on the resin instead of a number, to show that the block had been examined and did not belong to the group being studied. Once each block had been numbered it was photographed (when possible) and recorded. A sketch map was produced showing the location of each numbered block. Each block was assessed and a priority assigned for its treatment according to its condition and situation. Each block was photographed before and after treatment and records kept of its condition and treatment.

2.7.4 Clearing the blocks

The first process was clearing, starting from the north side of the block area, to remove debris from the bases of the blocks and to reveal them. Some blocks had been stacked on top of each other or had fallen against lower ones. All the blocks were inspected and those needing clearing to reveal the decorated surface (Figs. 31 & 33) were dug out using a small trowel and hand tools, taking great care not to mark the surface of the stone. Grass was removed where it obscured the surface or was touching, growing next to or into the structure of the blocks (Fig. 32). Most decorated surfaces were given preliminary brushing with a soft brush to remove dirt and loose dust was blown off with a photographic puffer/blower tool. This revealed the surface for examination and photography by Dr. Karkowski.

|

Fig. 32: Egyptian workmen removing vegetation growing among blocks on "Ptah Hill. |

|

Fig. 33: Detached fragments from a block during conservation. |

Loose flakes which were found near a block or which became detached during the removal of soil and plants were lifted and left on top of the block to dry (Figs. 31 & 33). The surface of any breaks was cleared and allowed to dry. Where possible, the break surfaces on fragments and on blocks were cleaned with an artist's soft brush and a puffer-blower. Many blocks were so deteriorated that even this delicate treatment would have caused further loss of stone and powdering away of the surface.

Priority was given to the decorated front surface of the blocks. Most of the blocks concerned were carved in the time of Seti I in raised relief and in many cases traces of the paint were also preserved (Fig. 27). The blocks that were lying with the decorated face upwards were less in need of immediate treatment, although many showed considerable structural splitting and often great displacement of large fragments (Fig. 34). The best remedy for this condition would be to lift them from the irregular ground surface and place them on clean, firm mastabas where they could be realigned. It was not possible to achieve this during the spring 2000 season, but it is recommended that the blocks be relocated as soon as is feasible.

|

Fig. 34: Block split into several pieces. |

The blocks whose decorated surface was close to or actually under the ground required immediate treatment. The first concern was to clear away the dirt from around the decorated surface. While this was being carried out it became clear that the grass and thorn bushes were contributing significantly to the immediate deterioration of the blocks. It remains a priority to remove these blocks from the salty, moist ground where the plants can grow around them. Although the halfa grass (Desmostachya bipinnata) and camel thorn (Alhagi graecorum)64 ' had been killed with a herbicide some time previously, the dead plant stems that remained were still causing considerable problems for the blocks. In the morning, the presence of extra moisture in the air may have caused the stems to expand, acting as a wedge which displaced fragments. When detached and displaced fragments were removed, it was frequently found that the space between the fragment and the block was filled with a dense mass of plant material, which was often wet to the touch.

A phenomenon was noted which might be related to this. Several blocks were found to have a hard concretion of salts and dirt on the surface (Figs. 35-36).

| Fig. 35: Block with a heavy concretion of salt before consolidation and cleaning. |

|

Fig. 36: Detail of same block before conservation. |

When this was removed mechanically from the surface of block 175 a sample of the dry salt crust was kept in a small plastic bag which was sealed with a plastic zip-lock storage bag and left in the sun while work progressed. A few hours later it was noted that the salt had deliquesced in the heat, turning into a liquid. In the cool of the evening it had solidified into a crystalline substance. Further samples were kept and the phenomenon noted more carefully. On this occasion, the salt sample was sealed at 7.40 am. By 8.20 the sample had begun to soften and the inner surface of the bag was clouded with condensation. By 10.05 am the contents were almost completely liquefied and remained so for the rest of the day.

Remains of wooded blocks, used as risers, probably by Legrain, were discovered. These were present just as brown marks in the soil, although some had remains of recognizable wood fibers. Workmen employed by the S.C.A. at Karnak assisted the work of clearing (Fig. 32). Jane Hill and Tammy Hillburn assisted with excavation.

2.7.5 Consolidating fragile stone

As each block was cleared, any loose fragments found in association with it were separated and removed for treatment. It was found that consolidation with a 5% solution (weight/volume) of Paraloid B72 in acetone would give almost immediate strength to the crumbling sandstone. The Paraloid solution was applied by allowing it to flow gently onto the surface from the nozzle of a polythene wash-bottle until the area was sufficiently saturated. This allowed a continuous stream of consolidant to diffuse into the fragile area. Both the detached fragment and the very fragile area on the main block from which the fragment came were consolidated this way. Great care was taken to make sure that the fragile areas were sufficiently supported during the consolidation, since they are at their most vulnerable while the consolidant is still in solution. Wherever possible, the consolidation was carried out during the cooler part of the day to slow down the rate of evaporation of the solvent. When treatment had to be carried out in hot conditions, especially where the surface was in direct sunlight, a sheet of Mylar foil coated plastic was laid over the block to keep the treated area as cool as possible. This significantly slowed the rate of evaporation of the solvent and increased the penetration and diffusion of the consolidant, even in the hottest part of the day. On one occasion the bottle of acetone supplied proved, when opened, to contain amyl acetate instead. This could be useful although it would not normally be the first choice of the conservator. Fragile areas on blocks that were no longer buried but which displayed deterioration were treated in a similar manner with the Paraloid B72 solution being injected into the cracks and fissures in the crumbling strata.

It was found that the action of salt crystallization that weakens the stone particularly at or below the ground level was greatly enhanced by the growth of grass and other plants. These not only attract and hold moisture in the immediate area but also physically break up the. On many occasions it was found that a grass stem had grown into a small crack and had acted as a wedge to split the stone (Fig. 30). It was found in areas of sever salt disintegration of the sandstone that the grass had grown in the fragile stone as it would in a compact soil. Damage from the grass was found to be rapid and dramatic. If a previously consolidated area which was threatening to separate from the block detached within a day or so of application it was invariably found that there was significant grass intrusion directly behind the treated fragment.

In a few cases a salt and dirt crust was found over the surface of a block (Figs. 35-36). This was removed using a combination of an aqueous cleaning solution and mechanical means. The solution consisted of a mixture of equal parts of clean tap water and acetone with 0.5% Synperonic (a non-ionic detergent) and a few crystals of sodium hexametaphosphate (a de-calcifying agent). The acetone was added to increase the rate of evaporation and so reduce the penetration of the water into the stone. Only a small amount of distilled water was available. The tap water was tested with a conductivity meter and was found to have the same or a slightly lower level of impurities as the distilled water so it was judged safe to use in this case. The mechanical removal of the salt and dirt crust was effected with a specially shaped round-bladed knife and a scalpel. The surface of the stone was then brushed with a soft brush to remove any remaining loose salt fragments and to prevent any semi-soluble salt crystallization forming on the surface as the stone dried (Figs. 37-38).

|

Fig. 37: The same block after conservation and cleaning by Richard Jaeske, March 2000. |

|

Fig. 38: Detail of the block after conservation and cleaning. |

2.7.6 Testing and use of Wacker Silane

30 liters of Wacker silicic acid ester (hydrophobic form, used without catalyst) were available on site. Tests were made to compare the effect of this compound with the acrylic resin consolidant. The solution was applied in the same manner as the Paraloid B72 solution, using a wash bottle to gently pipette the solution onto the surface. On a block 30cm x 20cm x 20cm 450-500 ml of Wacker silane was applied. The treated area was covered with Mylar reflective film for 2.5 hours during the hotter part of the day, but the area was still very fragile after treatment.

The effects were less dramatic than those obtained using Paraloid B72. The Wacker silane did not provide significant cohesive effect after the first application had hardened. A reasonable amount of structural strength was attained in a fragment 3 or 4 days after one application. This might be satisfactory for consolidation of some fragile sandstone, but in this case the condition of the blocks and the need for an almost immediate improvement in strength, adhesive and cohesive effects meant that the effect of the Paraloid was preferred. This was particularly important on the break surfaces of the main blocks near the ground, which were often in vertical or overhanging areas. The extreme fragility and imminent threat of collapse of the stone material required the use of a consolidant with very rapid bond strength. The Paraloid B72 resin exhibited tackiness and a cohesive effect, binding the deteriorated stone, within seconds of application. As the consolidant hardened subsequently it also demonstrated greater strength than the Wacker silane.

2.7.7 Safety Issues

Care was taken with regard to three main hazards:

1) Physical damage to the blocks and to the conservator through lifting and maneuvering of the heavy blocks, especially in awkward situations.

2) Dust from the blocks and the surrounding area. When cleaning the surface a particle filter mask was used.

3) Solvent from the consolidation treatment and the cleaning solution. When using solvents, an organic vapor mask was used.

2.7.8 Small Fragments

Small fragments which were in accessible areas and which formed a good join with the block were reattached using a viscous solution of Paraloid B48 acrylic resin (a copolymer of ethyl methacrylate and methyl acrylate) in acetone as adhesive. Due to the great displacement of many of the separated fragments and the disruption of many areas of the blocks it was not possible to re-attach all the fragments until the blocks can be moved to a better location. The remaining fragments were therefore retained separately, safely packed in cloth bags clearly labeled. The bags were made locally, to the conservator's specifications, of unbleached muslin 50cm x 80cm bags with a simple drawstring closure of strong cord, probably polypropylene. Tyvek labels were not available, and card labels could be torn off so the bags were identified by marking with permanent lightfast insoluble marker pen on the front. Each bag was labeled "Karnak 2000" with the block number in a rectangle and the number of fragments placed in the bag. A record photo was taken of each group of fragments with their bag as a reference label before the pieces were bagged. The 20 carefully labeled bags were placed in a locked storage magazine near the Akhmenu Court in Karnak temple under the supervision of our assigned inspector from the S.C.A. Two red quartzite statue fragments were also discovered and were put in a bag in the same store.

2.8 2001 FIELD SEASON

Tragically, the Karnak Hypostyle Hall Project's founding Director, Prof. William J. Murnane, died unexpectedly in November 2000. As a result, Dr. Peter Brand took over his posts as Director of the Project and as a Professor of Egyptology and Ancient History at The University of Memphis. Despite the loss of Professor Murnane, our work at Karnak continues. The Project worked at Karnak from mid January through early April. The sole member of the expedition was Dr. Brand.

As a result of the shocking acceleration of the salt damage in the Hypostyle Hall, Professor Murnane had decided, shortly before his death, to launch an additional season of salvage epigraphy in early 2001 focusing on the most endangered reliefs on the lowermost register of reliefs inside the Hall (Figs. 5A-C & 39). This program of "salvage epigraphy" had already begun during his last season in 2000 when we had specifically focused our collation efforts on the south exterior wall along the bottom register which was decaying more rapidly than any other part of that wall.65 Inside the Hall, our prime concern was various ritual tableau scattered along the bottom registers of the interior walls, especially the south half of the west wall (= the bottom of the east face of the Second Pylon's south tower).66 Next in order of priority are badly salted reliefs of Seti I at the north-east corner (= against north-west end of the Third Pylon Facade), all being on the bottom register (Fig. 40-41).67

|

Fig. 39: Members of the Great Ennead from the west interior wall, south half, bottom register. A concretion of insoluble salts covers much of the surface. In other places, the relief is powdering and exfoliating. Photo taken 2001. |

|

Fig. 40: Offering list from a barque scene of Seti I, west wall, north end, as it appeared in the 1930s. Photo courtesy the Oriental Institute archives, University of Chicago. |

|

Fig. 41: Detail of the same offering list in 2001. Most of the damage is quite recent. |

By the end of the 2000 season, preliminary drawings of the most endangered and unstable reliefs along the south half of the west wall had been completed for all but three of them (Figs. 42-43).

|

Fig. 42: Ramesses II, (usurped from Seti I), offers to Amen-Re. Preliminary drawing from west wall, south wing, bottom register. |

|

Fig. 43: Ramesses II offers cloth to Amen-Kamutef. Preliminary drawing from west wall, south wing, bottom register. |

The work was also one of the first major tests of new modifications which we had recently made to our epigraphic methodology, building on the "Chicago House method."68 We replaced our traditional 40.6 x 50.8 cm photographic enlargements with larger 61 x 51 cm ones. This allowed us to better capture the often intricate details of the fine relief carvings on the interior walls and to ensure better accuracy of the preliminary drawings, thereby making collation easier and faster. The larger scenes were also printed on two or more enlargements, with the especially wide barque procession scenes spread out over four or more photographic enlargements with some overlap. Rather than directly pencil the enlargements, we now made the initial drawings on semi-transparent Mylar plastic film (calque). Due to the ongoing damage that these reliefs had suffered in the several decades since they were first recorded by Nelson, we opted to use archival photographs graciously provided to us by Chicago House which also gave us the use of its senior photographer gratis in order to custom print these to our specifications.69

In some cases where the reliefs showed little or no decay since the Chicago House photographs were taken in the 1930s, we used the same sized photographic enlargements made by the photographic department of the Franco-Egyptian Center at Karnak from a comprehensive photographic survey of the Hypostyle Hall undertaken by its chief photographer Antoine Chéné.70

No major discoveries were made in recording these reliefs, as they had been carefully examined by various scholars investigating the chronology of the Karnak Hypostyle Hall and the hypothetical coregency of Seti I and Ramesses II.71 Careful observation and recording of these reliefs anew did turn up many fine technical details not captured in Nelson's drawings such as the survival of plaster and traces of paint and recutting of relief.

2.9 2002 FIELD SEASON

The Karnak Hypostyle Hall Project of The University of Memphis worked at Karnak from May 26 to June 29, 2002.72 The main objective of the season was to continue collation of war scenes of Ramesses II on the south exterior wall of the Hypostyle Hall in order to produce facsimile drawings of these reliefs. Initial drawings of these reliefs were first made in 1995.73 We had begun collation of the drawings in 1999 under the Project's late Director, Professor William J. Murnane. In 2000, we concentrated on the lowest register of the south wall because the scenes along the base of the wall, especially the historically important list of foreign place names, were rapidly decaying despite several conservation treatments of the reliefs in recent years aimed at preserving them.

By 2002, some of the name rings of the topographical lists from the great triumph scenes flanking the south gateway had become illegible (Fig. 44).

|

Fig. 44: Decaying name rings, south exterior wall. |

At the end of the 2002 season we had completed collation of approximately 70% of the scenes on the south wall including the palimpsest of the Battle of Kadesh which was inscribed by Ramesses II on the south wall before he suppressed the Kadesh reliefs and replaced them with scenes of his other wars in Syria (Figs. 6 & 19). The most interesting and difficult challenge has been to recover traces of the suppressed "Bulletin" of the Battle of Kadesh narrative. This is inscribed in several columns of texts immediately to the west of the south gate of the Hypostyle Hall. This erased version of the "Bulletin" is especially interesting since it includes the later portions of the text which is badly damaged in other known versions. Superimposed over the "Bulletin" is a large triumph scene of the king smiting foreign enemies in the presence of the god Amen-Re (Figs. 18 & 21) and above this part of a war scene at the top of the wall and immediately adjacent to the south gate. More specifically, traces of the Bulletin are found superimposed over part of a rhetorical speech of the god Amen, in several name rings from the topographical list (Fig. 23), and also over a representation of an enemy fortress in the battle scene above the triumph scene (Fig. 45). Most difficult to disentangle were the areas where columns of texts from the "Bulletin" lay under the vertical columns of text from the triumph scene and under the name of a fortress in the battle scene at the top of the wall. In these areas, the scale of the two sets of hieroglyphs makes it possible to separate the two sets of texts. Many of the hieroglyphs from the "Bulletin" often retain traces of plaster used to suppressed them (Fig. 45).

Although only traces of the erased text survive, we have been able to recover some interesting information. The best preserved section comes from the end of the "Bulletin." It contains some variations from the other exemplars of this text. For example, in other versions, the king is compared to the god Atum, but in the Karnak text, the same passage compares him to Amen. It is hoped that closer examination of the traces of the palimpsest we recorded this season will allow us to make further restorations of the text of the "Bulletin."

To date, our collation of the palimpsest of the Battle of Kadesh reliefs and the "Bulletin" has revealed many more traces than earlier investigators like Breasted, Kuentz and Kitchen had found.74 The Kadesh reliefs were not completed before Ramesses II decided to replace them with other war scenes. To the west of the central gateway is part of the camp scene showing the pharaoh seated on his throne and hearing from his generals and ministers that the Hittites were nearby. Below this is the scene of the captured Hittite spies being beaten by Egyptian soldiers and a long row of Egyptian soldiers below. There is also an isolated scene of an Egyptian soldier cutting off the hand of a fallen Hittite soldier. Along the base of the entire wall is the river Orontes depicted as a horizontal band with a zig-zag pattern of water inside. Except for this river, all the other traces of the Kadesh palimpsest are close to the central doorway.

2.9.1 Salvage Epigraphy Inside the Hypostyle Hall

Since the 1999 season, the Hypostyle Hall Project has made a special effort to do "salvage epigraphy" by recording reliefs and inscriptions that are most in danger from groundwater and salt damage. In 1999 and 2000, we focused on the battle scenes along the bottom of the south exterior wall which showed rapid deterioration from salt damage despite conservation treatments by the Centre Franco-Égyptien in 1998 and 1999. In 2001, our salvage epigraphy began to record damaged reliefs along the bottom of the west interior wall in the southern part of the Hypostyle Hall which is the same as the east wall of the south tower of the Second Pylon.75 These reliefs had begun to decay rapidly in the late 1990s and most of them were recorded in 2001.76

In the 2002 season, our artist Lyla Pinch Brock continued the process of recording these endangered scenes on the west wall and also others that are beginning to decay on the south wall and another scene near the north-east gateway of the Hypostyle Hall. These drawings were made by tracing with pencil on Mylar on top of archival photographs made by Chicago House in the 1930s from the north-east gateway and the west wall, and some others made by Antoine Chéné in 2000 from the south gateway. The Chicago House photographs were used where there is more damage to the reliefs today than when the photos were originally made. The photographs of Mr. Chéné were used when there was no significant decay to the reliefs. The reliefs on the south gateway are still in very good condition, but there is evidence that they are beginning to decay. The reliefs on the west wall have been treated repeatedly in the past four years by conservators from the Centre Franco-Égyptien. The damage to these reliefs has been slowed down but is still progressing. Several scenes on the west, south and east wall were recorded in this manner,77 along with a scene on the small throne shrine of Ramesses II attached to the Second Pylon at the entrance of the Hypostyle Hall.78

2.9.2 Identification, Measurement and Recording of Blocks

By Dr. Janusz Karkowski

This part of the Great Hypostyle project was started in 2000 when 202 decorated blocks were documented. The departure point for this work was an inventory prepared by Dr. William Murnane consisting of sketchy hand drawings and few additional remarks concerning the kind of relief, and their place in the storage area. Whenever possible the blocks were photographed, but 75 blocks and fragments had to be traced using plastic film.

Before the 2002 season the photographs were scanned and enhanced using Adobe Photoshop 5.5. They were reduced to a scale of 1:5 and angular distortions corrected. The tracings were photographically reduced to 1:5 scale. On the basis of this scaled documentation the preliminary classification was made:

1) Blocks with the original sunken relief in small scale from the topmost register of the eastern wing of the north wall.

2) Blocks with the original sunk-relief scenes in larger scale from the third register of the northern wall.

3) Blocks with the original low relief reworked into the sunken relief.

4) Remaining blocks decorated in sunken relief.

5) Blocks with the original low-relief scenes in small scale from the topmost register of the north wall.

6) Blocks with the original low relief scenes in larger scale from the third register of the north wall.

7) Blocks with the modified low relief scenes in larger scale from the third register of the north wall.

8) Blocks decorated in the original low relief with king facing left from the south wall of the east antechamber

9) Blocks from the lintel of the northern gate.

10) Blocks that may come from two additional windows in the east wall.

11) Fragments of pillars of the clerestory windows.

During the 2002 season the scaling of the photographs of the blocks recorded in 2000 was rechecked. This resulted in some corrections and permitted a more detailed classification of blocks. In addition, all the remaining 73 blocks from the inventory were documented either photographically or by tracing. At the same time ten more fragments were identified and recorded in the open storage areas at Karnak; these may come from the walls of the Great Hypostyle Hall.

The preliminary results of the research into the blocks has resulted in the discovery of the exact location of a growing number of blocks in particular walls and other architectural elements of the Hypostyle. At the moment the additional measurements and the analysis of the decoration permits us to restore the sequence of all the scenes in the topmost register of the south wall eastwards from the central doorway, and ascribe to it 25 blocks. The corresponding western wing of the same wall is not in as good a state of preservation, but three blocks could be ascribed to it this season. The identified fragments of the lintel of the doorway in the north wall permit the restoration of its size and of the composition of its decoration. Newly identified fragments and the more accurate measurements of the previously documented blocks from the pillars between the clerestory windows permit the distribution of the blocks to the south or north of the Hall's central axis. There is a chance that they may be ascribed to four specific missing pillars after the documentation is processed and analysed.

The blocks stored on the hill north of the Hypostyle Hall were only partially analysed. This is due to their inaccessibility, making the recording and measurements extremely difficult and time consuming. The abundant thorny plants that screen the decorated surfaces worsen the situation. Their examination will be much easier when the blocks are transferred to the new mastabas in the northeast corner of the Great Enclosure, scheduled for completion in the summer or fall of 2002.

The epigraphic corrections of the decoration of the blocks have begun. This is a necessary stage preceding the final drawings to detect all the important details that may not be clear on the photographs or were overlooked during tracings. Full collation of drawings of the blocks by a team of epigraphers is planned for future seasons.

3.0 EPIGRAPHIC METHODOLOGY

As a former member of Chicago House, William Murnane endeavored to produce a record of the Hypostyle Hall reliefs approaching the highest standards of the Epigraphic Survey. With resources much smaller than Chicago House it was obvious that a somewhat scaled down process would be necessary. Initially, the Project used a slightly modified version of the Chicago House method. Scenes were traced in pencil on 40.6 x 50.8 cm photographic enlargements by epigraphists. Next the photographic emulsion was chemically bleached out leaving only the pencil drawings. From blue prints of these drawings, collation sheets were made on 21.4 x 43.5 cm. sheets of paper to which was affixed a small portion of a blue print copy of the drawing. From these collation sheets teams of epigraphists carefully checked the drawings against the wall, making adjustments to the drawings, detailed notations of the necessary changes, and often sketches of individual hieroglyphs and other detailed elements of the reliefs. The objective was not merely to record the full epigraphic and iconographic details of the reliefs, but also to reproduce faithfully their paleography and artistic style.

From these collation sheets, the original drawings were next fully corrected in pencil by the staff artist and the adjusted drawings were checked against the collation sheets by the Project Director. The Director produced a list of any discrepancies he found to be further corrected by the artist. This back and forth process of consultation was repeated until all questions and/or discrepancies had been settled, and in some more difficult cases, the collation sheets and completed drawings were re-examined at the wall during later seasons. In the last stage of this process the final edition of the drawings were inked by tracing them on sheets of Mylar, thus preserving the original penciled enlargements.

After the 1997 season, we developed a further modification of our working method. The need to conserve precious field time and financial resources, in particular, inspired a new approach. The size of the photographic enlargements on which the drawings were based was increased to 51 x 61 cm. Now, instead of tracing directly on the enlargements in the field, the initial drawings were produced by an artist in North America by tracing the drawings in pencil on Mylar laid over the photograph enlargement. This new method was advantageous for a number of reasons:

(1) It eliminated the need for the costly process of bleaching out the enlargements. Likewise, duplicates of the enlargements were not needed.

(2) All of the original drawings could be made by an artist in the controlled environment of a studio instead of in the field.

(3) By working at home, the expense of supporting a staff in the field to complete the initial drawings was eliminated. This also allowed precious field time to be devoted to the crucial process of collation.

Following a successful trial of this process in 1999 on a scene from the north gate, the new method was used to great advantage in collating drawings of reliefs on the south-east corner of the Hypostyle Hall in 2000. The result was a savings of months of field time and production of more accurate drawings. A further advantage of this process arose from the fact that the original photos were never bleached away. It was now possible to check the preliminary drawing on the Mylar (calque) by removing it from the photo or by inserting a sheet of paper between them. This allowed the artist to more easily refine his work and to inspect the drawing for any stray elements which had accidently been omitted. Such details were easy to miss when drawings in pencil are made on a black and white photograph.79 After first collation, the proportional accuracy of the artist's corrections to the drawings could be checked by overlaying the drawings on the photograph. This prevented many subtle inaccuracies from creeping in during the correction process. Finally, during the inking process, overlaying the drawing on the enlargement makes it easier for the artist to render various types of damage— hacking, erosion and incidental damage— more accurately and distinctly rather than drawing them freehand.

4.0 PRELIMINARY EPIGRAPHIC AND HISTORICAL FINDINGS

4.1 Eastern Passageway of the Second Pylon

When this project resumed its work at Karnak in 1991 the only substantial block of scenes on the walls which remained unrecorded within the interior of the Hall was the material inside the passage through the Second Pylon. This structure that predates the Hall itself by as much as a quarter-century, for the Second Pylon itself was constructed by Horemheb.80 The western half of the passage through pylon, including the mountings and "shadow" recesses for the gigantic double doors of this gateway, was substantially rebuilt during the third century B.C.E. and does not concern us here. At the eastern end, however, both side walls81 are covered with five registers of scenes, surmounted on either side by a frieze of royal cartouches flanked by serpents (Figs. 7, 46-52). Making them a priority was not only a matter of tidiness (to bridge the gap between the material inside and outside the building) but of scientific concern, particularly with regard to the our understanding the "prehistory" of the Hall itself.

|

Fig. 46: Part of a cartouche frieze from the top of the western passageway, north wall. Facsimile drawing by Peter J. Brand, inked by Lyla P. Brock. |

|

Fig. 47: Western passage, relief at the east end of the bottom register of the passage, south wall: Ptolemaic figure of Ramesses III. |

|

Fig. 48: Western passage, south wall, upper frieze and first register (both reinscribed for Ramesses II, in raised relief, during the Ptolemaic period). |

|

Fig. 49: Western passage, fourth register (western scene): Ptolemy VI (his figure usurped from its original owner) is led into the temple by Khonsu. |

|

Fig. 50: Ramesses II offers bouquets to ithyphallic Amen-Re. Western passage, south wall, first register. Facsimile drawing by Peter J. Brand, inked by Lyla P. Brock. |

| Fig. 51: Ramesses II (usurped from Ramesses I) led by Atum. Western passage, south wall, second register. Facsimile drawing by Peter J. Brand, inked by Lyla P. Brock |

|

Fig. 52: Sunk relief cartouches of Ramesses II surrounded by raised relief of Ptolemy VI. Western passage, north wall. Traces of a quail chick at the bottom of the nomen and of a larger sun disk surrounding the final one in the prenomen attest to the original presence of Ramesses I's name in raised relief. NB: the interior level of these cartouches is higher than the surrounding Ptolemaic relief, indicating that this surface is original. |

The king whose name was inscribed inside the cartouches in the friezes at the top of both walls is Ramesses II (Figs. 46 & 48), who is also the celebrant in most of the scenes carved below: since such cartouche friezes generally define the identity of the ruler responsible for the structure in question,82 it would seem that those who carved this passage in antiquity regarded it as Ramesses II's work.83 In no fewer than three of the episodes below, however, the officiating king is Ptolemy VI (180-145 B.C.E.) (Fig. 49). Moreover, since the carving throughout this area exhibits numerous features compatible with the style used in Egyptian temples of the Hellenistic period, it stands to reason that these reliefs were actually executed long after the time of Ramesses II, during the second century B.C.E.

Opinion had been divided as to whether these scenes were originally carved in the Ptolemaic era84 or only restored at that time based on a Nineteenth Dynasty prototype.85 In any case, the clash between the apparent date of these poorly documented carvings and their prevailing content (originating about 1100 years earlier) made them prime candidates for recording. Thus, when the expedition resumed its work at Karnak in 1991, we decided to begin by attempting to resolve this question.

Close examination of the reliefs revealed that they were indeed based on an earlier version, which must have been badly damaged when the roof of the passage collapsed in late antiquity.86 The repairs in this section did not confine themselves, however, to substituting reliefs in the names of contemporary Ptolemaic rulers, as happened on the outer gateway and in the recesses for the door leaves of the Second Pylon.87 Instead, the Hellenistic restorers made an effort to recreate most of the original scenes at the east end of the passage, diverging from this program only when they inserted Ptolemy VI, the sponsor of this repair, into the compositions. The result is an amalgam, reproducing something of these walls' early appearance (though, admittedly, in the current style) while integrating into them not only elements of the original carving but also additions that were made at various periods. What these changes were will be clearer following a summary of the decoration of the passage as it currently exists.88

4.1.1 North Wall

Top: Cartouches of Ramesses II, in raised relief that is manifestly Ptolemaic instyle, protected by cobras. The king's praenomen is Wsr-mAat-Ra stp.n.Ra (as it is everywhere else on these walls); his nomen is Ra-ms.s mri-Imn. NB: all elements in these scenes are in raised relief except for the cartouches and Serekhs containing the names of Ramesses II in the lower registers of these walls. On both the north and south walls, the raised relief cartouches are found in the top friezes and the upper register of scenes.

Upper register:

(west) [King] offers nw-jars to standing Amen-Re. The figures are carved in raised relief, as are all others on these walls. Traces of the earlier version are especially strong in this scene, demonstrating that the later Ptolemaic version is essentially a copy of the original design.

(east) Ramesses II offers flowers to ithyphallic Amen-Re. His names, like the figures, are carved in raised relief, as is his nomen is Ra-ms.sw mri-Imn. This form of the nomen occurs in all the scenes on both wall, although the cartouches in the top friezes are all Ra-ms.s.

Second register:

(west) Ramesses II (names sunk) is led into the temple by Monthu and the goddess Tchenenet.

(east) Ramesses II (names sunk) offers a libation to standing Amen-Re.

Third register:

(west) Ramesses II (names sunk) offers flowers to ithyphallic Amen-Re.

(east) Ramesses II (names sunk) kneels beside the Ished Tree in front of Atum enthroned, while Sefkhet-aabwy stands behind the king and writes on the tree's leaves.

Fourth register:

(west) Ptolemy VI (names raised) is led into the temple by a hawk-headed Khonsu.

(east) Ramesses II (names sunk), with Mut standing behind him, kneels before enthroned Amen-Re and receives jubilees from him.