Benjamin Hooks, Ronald Reagan and Economic Inequality

by William C. Love

On March 10, 1981, Benjamin L. Hooks, Executive Director of the NAACP, stood before

the third annual NAACP Legislative Mobilization at a Baptist church in Washington,

D.C. to address what to him were the shortcomings of newly inaugurated president Ronald

Reagan’s political agenda.

On March 10, 1981, Benjamin L. Hooks, Executive Director of the NAACP, stood before

the third annual NAACP Legislative Mobilization at a Baptist church in Washington,

D.C. to address what to him were the shortcomings of newly inaugurated president Ronald

Reagan’s political agenda.

Reagan in his inaugural address, less than two months earlier, had presented his case that the two main challenges to the current United States economy were runaway inflation and federal regulation, both of which stemmed from the governmental overreach of the 1970s. To stimulate the economy, Reagan proposed policies he believed would decrease the role of government and augment the private self-rule of its citizens, including lowering marginal tax rates and ending the manipulation of government by special interest groups. To quote one of Reagan’s most memorable lines, “In this present crisis, government is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem.”

Hooks’ rebuttal to Reagan before the Legislative Mobilization was not a clarion call for more governmental intervention in the lives of African-Americans. Rather, Hooks argued for the inevitable wealth disparity that would continue should we approach the United States economy as an egalitarian market place, where all citizens exercise their self-rule equally.

Hooks noted in his speech that “We are in a dual economy, because we are still in a dual society—still separate, still unequal.” The dual economy was not simply a matter of black vs. white, but the divide between blacks and whites on the macro-economic level highlighted the disparities of the dual economy. The average income for white families was 18,662 dollars a year, whereas black families earned on average 10,879 dollars a year, 40 percent less than white families. Considering that 5% of the population owned 1.5 trillion dollars of the 2 trillion dollar economy, Hooks declared that “no one can read such figures and not recognize that we have a dual economy.” He continued, “If that is so, then we must take separate approaches to the duality with the single purpose of bringing equity and unity to the whole.” Thus, for Hooks, the economic numbers did not suggest that the American economy or society had bolstered social equality enough for the free market alone to dictate social mobility and household incomes. Of course, the federal government should spend its money cautiously, taking every step to eliminate abuses, but to use Hooks’ words, “essential categorical and targeted programs” should be kept in the interest of eliminating radical inequality and promoting national unity.

Hooks’ public dispute  with the policies of the Reagan administration was one of the most important aspects

of Hooks’ tenure with the NAACP in the 1980s. Indeed, in Roy Finkenbine’s Primary

Sources in American History: Sources of the African-American Past, Finkenbine introduced

an excerpt from one of Hooks’ 1983 speeches by noting that during the 80s, Hooks was

a “major critic of the Reagan administration’s avoidance of important racial questions

and trimming of major social programs, including those designed to aid the poor.”

with the policies of the Reagan administration was one of the most important aspects

of Hooks’ tenure with the NAACP in the 1980s. Indeed, in Roy Finkenbine’s Primary

Sources in American History: Sources of the African-American Past, Finkenbine introduced

an excerpt from one of Hooks’ 1983 speeches by noting that during the 80s, Hooks was

a “major critic of the Reagan administration’s avoidance of important racial questions

and trimming of major social programs, including those designed to aid the poor.”

Much of Hooks’ continued criticism of the Reagan administration may well have been triggered by the anxiety felt by much of the black community upon the election of Reagan. The anxiety was so high that Hooks called a special press conference on November 22, 1980 to address the “new hysteria that prevails in many of the Black communities of our nation following the election of the Reagan administration, and more particularly the election of a very conservative Senate and House which caused the displacement of many of the most liberal names that Blacks have come to rely upon over the years.” Hooks’ language throughout the press conference was quite strong. He argued that “it is unfortunate, it is pathetic and tragic that once again Black people and their sympathetic white allies are called upon almost single-handedly as a group to defend the great American idea against those who hold high office who would spit on the flag, tramp on the constitution and crumble the Bill of Rights into nothingness.” Still, Hooks urged the Reagan administration to engage in talks with the NAACP about policy matters so that racial progress was not reversed. Hooks agreed that inflation and economic stagnation were crucial issues but a thriving economy does not necessarily benefit the black community. Thus, the NAACP would continue to lobby at the federal and local level for necessary grants to help the black community.

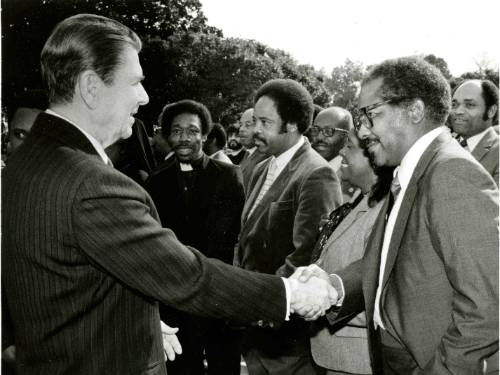

While stark differences continued between Reagan and the Hooks-led NAACP, a mostly respectul dialogue ensued between the two. Reagan continued open conversation with Hooks, including at least one White House visit by Hooks, and a representative of the Reagan administration attended the annual NAACP conventions, including Reagan himself in 1981 where Reagan gave an address to the convention. In his address, Reagan assured the NAACP that his “Administration will root out any case of Government discrimination against minorities and uphold and enforce the laws that protect them. I emphasize that we will not retreat on the nation’s commitment to equal treatment of all citizens.”

Still, Hooks remained unconvinced of Reagan’s economic solutions for the black community.

One clear example is Hooks’ annotated copy of Reagan’s speech to the NAACP. When Reagan

asked “can the woman I saw on television . . . whose family had been on welfare for

three generations . . . believe that current Government policies will save her kids

from such a fate?” Hooks noted “alternate programs” as the solution, not the elimination

of welfare. Hooks even noted that American productivity stops growing because of greed,

not because of government intervention, as Reagan believed. When Reagan remarked that

“just as the Emancipation Proclamation freed Black people 118 years ago, today we

need to declare an economic emancipation,” Hooks noted simply “joke.”

Still, Hooks remained unconvinced of Reagan’s economic solutions for the black community.

One clear example is Hooks’ annotated copy of Reagan’s speech to the NAACP. When Reagan

asked “can the woman I saw on television . . . whose family had been on welfare for

three generations . . . believe that current Government policies will save her kids

from such a fate?” Hooks noted “alternate programs” as the solution, not the elimination

of welfare. Hooks even noted that American productivity stops growing because of greed,

not because of government intervention, as Reagan believed. When Reagan remarked that

“just as the Emancipation Proclamation freed Black people 118 years ago, today we

need to declare an economic emancipation,” Hooks noted simply “joke.”

It is difficult to know Hook’s exact views on Reagan and his policies. Hooks throughout his legal and political career remained close to, if not directly affiliated with, the Republican Party, a point a press member made to Hooks during his press conference on Reagan. Hooks also, in interviews and speeches, continued to say that he did not believe Reagan to be a racist. He even publicly praised the Reagan administration for extending the Voting Rights Act in 1981. It appears that in the end, Hooks simply believed that the Federal government had an important and targeted role to play in redistributing services and advantages to the African-American community that the country had denied them for so long. Since Reagan believed that government intervention always does more harm than good, an impasse between the two was inevitable.

Other Resources

- An NAACP Admonition To The Reagan Administration and the Dual Economy and the Administration Budget Proposals

- NAACP Executive Director Calls Reagan Economic Recovery Program 'Dismal Failure' Urges Congress and the People To "Save the Nation"

- Statement of Benjamin L. Hooks of NAACP on Proposed Federal Budget for Fiscal Year 1983