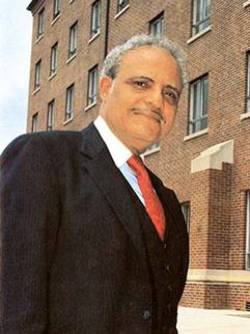

Ben Hooks: My Memphis Friend and Hero

By W. J. Michael Cody

I have lived in Memphis since my birth in 1936 and have always been interested in

the city’s history. Growing up, I knew the contributions of Ben Hooks and his family

in the early history of the city, but I did not have a chance to meet him until I

graduated from law school in 1961 and returned to practice law at Burch Porter & Johnson.

Lucius Burch was very much involved in civil rights with Dr. Hooks. During the early

1960s, and continuing up until Martin Luther King, Jr.’s death in 1968, I had many

occasions to work with and observe the accomplishments of Dr. Hooks, Jessie Turner,

Burch and others in bringing about the desegregation of department stores, transportation

systems, museums, parks, libraries and other public accommodations. Dr. Hooks was

the leading attorney on many of these significant breakthroughs in the process of

integrating facilities and systems in Memphis.

I have lived in Memphis since my birth in 1936 and have always been interested in

the city’s history. Growing up, I knew the contributions of Ben Hooks and his family

in the early history of the city, but I did not have a chance to meet him until I

graduated from law school in 1961 and returned to practice law at Burch Porter & Johnson.

Lucius Burch was very much involved in civil rights with Dr. Hooks. During the early

1960s, and continuing up until Martin Luther King, Jr.’s death in 1968, I had many

occasions to work with and observe the accomplishments of Dr. Hooks, Jessie Turner,

Burch and others in bringing about the desegregation of department stores, transportation

systems, museums, parks, libraries and other public accommodations. Dr. Hooks was

the leading attorney on many of these significant breakthroughs in the process of

integrating facilities and systems in Memphis.

One of my first meetings with Dr. Hooks was in the 1960s, when we were serving together on a local United Nations Club board. He asked me to go with him to see Mayor Henry Loeb with a request that the city declare a particular day in October of that year as “United Nations Day.” I went with Dr. Hooks and he eloquently made the case about the importance of the work of the United Nations, but the mayor steadfastly refused to grant our request on the basis that he did not like that the United Nations contained communist countries. Later in 1968, I worked with Dr. Hooks and others during Dr. King’s efforts to assist the sanitation workers in their struggle to gain recognition, better wages, and working conditions. What I will never forget is that after Dr. King’s death, riots and chaos broke out in major urban areas all across the United States, but Memphis was not affected quite so violently and dramatically. This was solely because Dr. Hooks, civil rights activist Jim Lawson and a few others quickly appeared on television to make an emotional plea to the public, and particularly the black community, not to react with violence to the death of Dr. King because such violence would be the last thing that he would want to happen. As a result of this fervent message from Dr. Hooks, Memphis was spared some of the violence and burning that occurred in other cities, including our nation’s capital.

Dr. Hooks was a dear friend, a riveting speaker, and a force for great good during his life in Memphis. No one left a stronger legacy for progress and fairness than Dr. Hooks. In every endeavor, his wife, Frances, was hard at work by his side. It is entirely appropriate that the Memphis Public Library bears his name. In this public library, which he helped integrate in the 1960s, his legacy for progress, education and decency is recognized by all who see and use it.

W.J. Michael Cody, a Memphis attorney, has served as United States Attorney, state attorney general, a member of the Memphis City Council and on the legal team for Martin Luther King, Jr. before his assassination in 1968.