Early Twentieth Century Memphis

Black Memphians developed a strong business and professional base within their communities. R.H. Tate, who died during the 1878 Yellow Fever epidemic, was one of the first African American physicians to practice in Memphis. By the turn of the century, forty other African American doctors, including two women (Georgia E. L. Patton and Fannie M. Kneeland) set up practices in the city. This core of black professionals also included seven dentists and twelve lawyers. Three of the latter argued anti-discrimination cases in local and state courts. In 1905, Memphis attorneys Josiah T. Settle and Benjamin F. Booth unsuccessfully argued Mary Morrison's challenge to Tennessee Hancock Law. The law mandated "separate but equal" on streetcars in the state's larger cities.

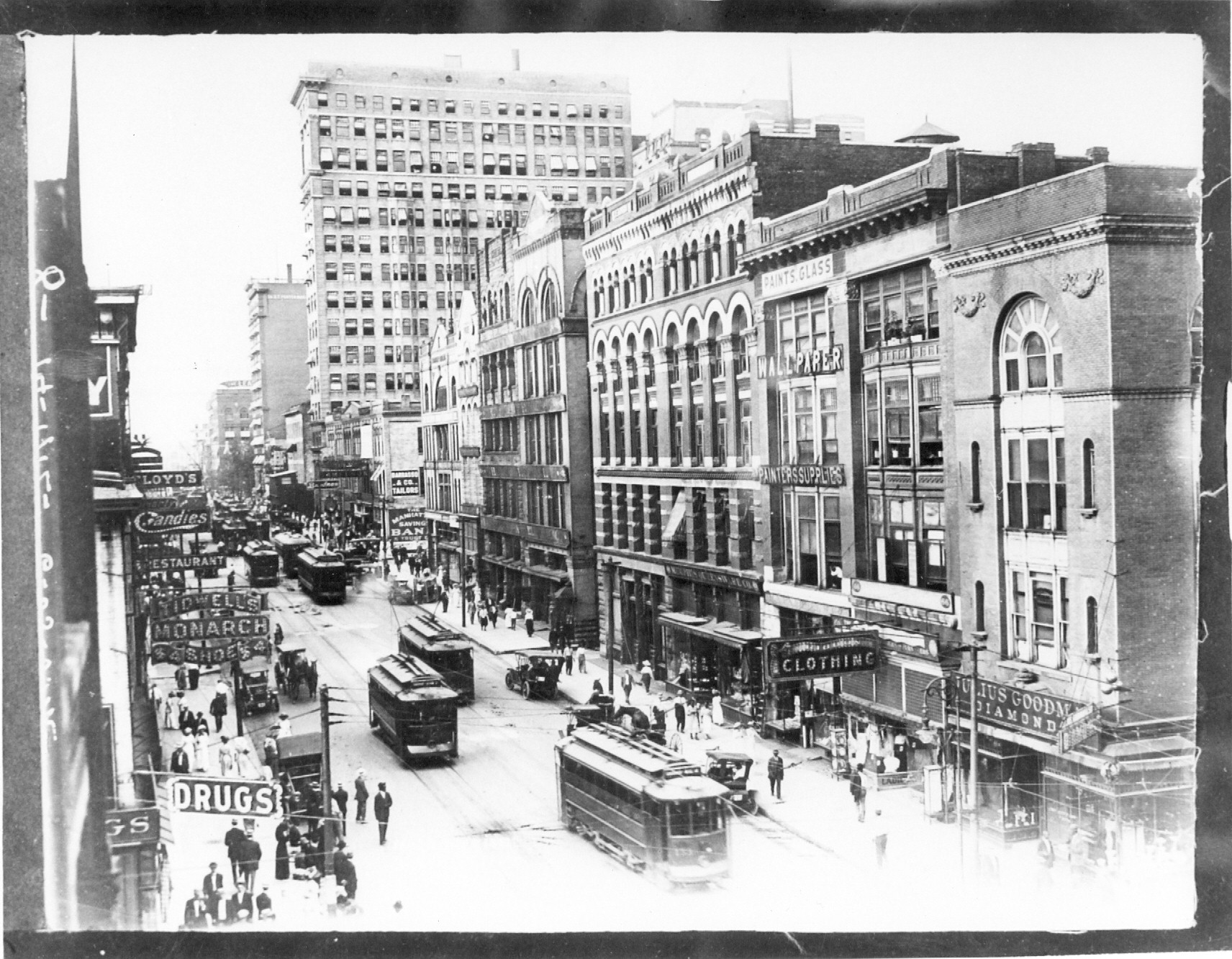

Memphis' large, active African American professional class was due in large part to the city's unique position as a river town, the commercial hub for the Mid-South region, and a center for black cultural and economic development. However, the challenges of the new century underscored the precarious nature of black political power in the Bluff City.