The Crump Era

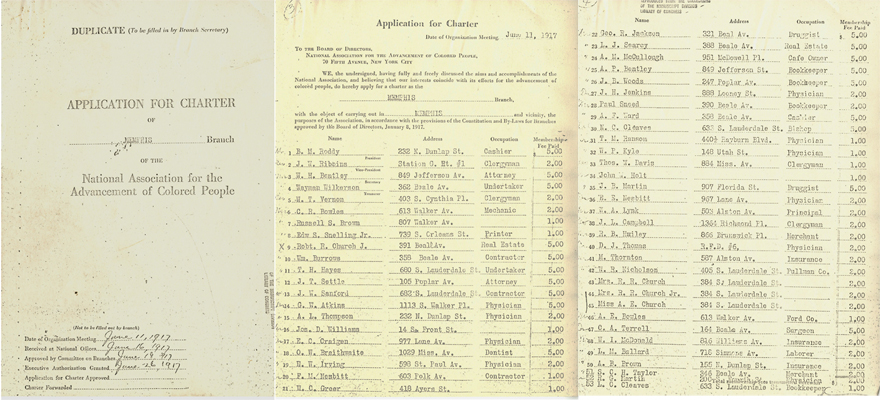

African Americans in Memphis, unlike blacks in other cities and towns in Tennessee, were never denied the right to vote. This was due to 1) the activism of black community leaders like Robert R. Church, Jr., who organized the city's Lincoln League and was a charter member of the Memphis chapter of the NAACP, which formed in 1919; 2) the work of Julia Hooks, grandmother of Benjamin Hooks, and other prominent African American women who encouraged black Memphians to pay their poll taxes so that they could continue to vote; and 3) Edward Hull Crump, the legendary "Boss of Memphis." In a political career that spanned over 50 years, Crump held a string of political offices, including mayor and the district's representative to the United States Congress. Crump was also an astute businessman and made millions. Politics, however, was Crump's first love. Unprecedented in his ability to garner and manipulate both the black and white vote, Crump created a formidable political machine that enabled him to control Memphis politics and exert considerable influence on Tennessee's gubernatorial and national presidential contests.

Crump was a progressive politician who was committed to improving the way city government operated. He worked for smaller, more efficient government and lower taxes. He was also concerned about child labor, public health and transportation, and parks and recreation facilities for black and white Memphians. Crump successfully instituted a commission form of government, reduced government bureaucracy and improved public services. He was fastidious about the city's appearance and tasked the office of public works with street cleaning, weed removal and trash pickup. He led the fight for and won consolidation of Memphis utilities, arguing that the move would save the people money. He also led the effort to build the Memphis municipal airport. While Crump tolerated no corruption by public employees, he created a group of campaign workers and supporters, known as the Crump machine, who accepted payoffs from saloons, brothels, or other illegal establishments to fund the activities of the Crump machine.

Crump was a staunch segregationist, but black Memphians understood their importance to Crump's Democratic Party machine. Black political leaders such as Robert Church, Jr. and his lieutenants negotiated with Crump and his lieutenants for improved city services, including parks and playgrounds, better police and fire protection, new schools, paved roads and sewers, and health care services such as John Gaston Hospital, a segregated hospital for blacks.

Memphis also had a flourishing black political cadre, whose leaders chafed under Crump's demand for absolute control of the political process. In 1938, Robert Church, Jr., a Republican who had supported the Crump machine in local elections, refused to support Crump's gubernatorial choice, Walter Chandler. Church, who controlled the Republican vote in Memphis and Shelby County, was a leader in the state and national Republican Party and, when Republicans held national office, could influence some patronage positions. But Church also benefited from Crump's largesse, having been exempted by the Crump machine from paying property taxes. When Church broke with Crump over Chandler's gubernatorial bid, Crump's administration seized his property over past due taxes. Church moved to Washington, D.C., and served on the board of directors of the National Council for a Permanent Fair Employment Practices Committee and later to Chicago. Church's home on South Lauderdale Street was later burned in a drill by the Memphis fire department.

Like Robert Church, Jr., J.B. Martin, a pharmacist on Beale Street and owner of the Memphis Red Sox, a Negro League baseball team, incurred Crump's wrath by asserting political independence from the Crump machine. Martin and his three brothers W. S. (a physician), A.T. (a physician), and B.B. (a dentist) were powerful figures within the black Memphis community. In 1940, J.B. Martin announced his support for presidential candidate Wendell Willkie, who opposed Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Crump's candidate. In retaliation, policemen were stationed outside Martin's South Memphis drug store to harass customers who tried to enter the business. J. B. Martin eventually moved to Chicago.

In building and sustaining the Democratic Party machine, Crump and his lieutenants encouraged and aggressively courted professional groups and both black and white civic clubs, the basis of community organizing in the city. African Americans in Memphis became experienced political operatives who, by the 1940s, increasingly challenged Crump's political authority and his support for segregationist practices.

The Crump machine was essentially defeated in 1948 with the election of Democrat Estes Kefauver to the U.S. Senate from Tennessee. Crump opposed Kefauver; the black community supported him. Two decades later, the absolute control of local politics and the insistence on the cheap, non-unionized labor of African Americans that was perpetuated under the Crump regime shaped the events that unfolded in the 1968 Memphis Sanitation Workers Strike.