Civil War and Reconstruction

During the Civil War

The racial dynamics of Memphis changed significantly between 1862 and 1865. During the Civil War, thousands of enslaved African Americans fled Mid-South farms and plantations for the relative security of camps and shantytowns in and around the Memphis. They began arriving in the months after the Union victory in the 1862 "Battle of Memphis." By 1864, more than 7,000 African American men from the camps had been recruited into the Union Army and trained in the Memphis area. The city's black population increased from an 1860 total of nearly 4,000 enslaved and free blacks, about 17% of the total population, to an 1865 black population of more than 16,000 freed men, women and children, or 39% of the city's total population.

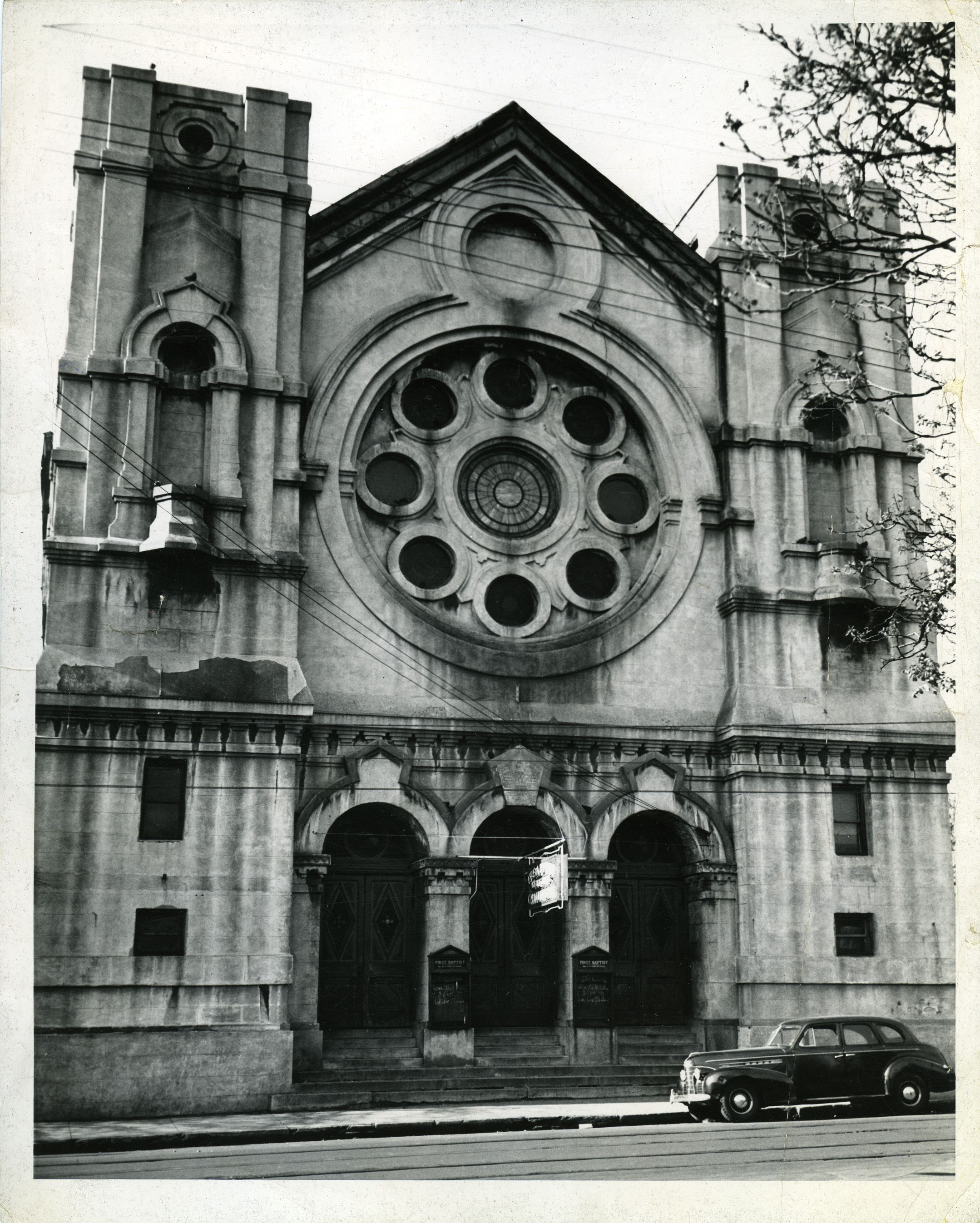

Although some freed people returned to Mid-South farms and plantations after the Civil War, others chose to remain in Memphis. Many congregated in the area around Beale, Linden, Turley, St. Martin, and Causey Streets, an area that some white Memphians derisively referred to as the "Negro Quarters." In May 1866, the competition for jobs and space coupled with the presence of black troops from the 3rd U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery regiment triggered clashes that led to a violent racial confrontation known as the "Memphis Massacre." Forty-six black and two white Memphians were killed, seventy-five were wounded, five black women were raped and over one hundred robberies occurred. Homes, churches, schools, and businesses in black neighborhoods were destroyed. These were rebuilt as the city, state, and nation underwent a period of social, political, and economic "reconstruction." In Memphis, African American community life matured in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Black congregations that had existed within white churches established independent facilities. By the early 1900s, the city's African American religious institutions included seven Christian Methodist Episcopal churches, five African Methodist Episcopal churches, one African Methodist Episcopal Zion church, twenty-six Baptist churches, Second Congregational Church and Emmanuel Episcopal Church. Secret societies, fraternal organizations, military groups, and social clubs were also prominent in turn-of-the-century Memphis.

Post Civil War

In the post-Civil War period, "sabbath schools" that had provided limited educational opportunities for the city's slaves and free blacks gave way to formal educational institutions. By the early 1900s, the city's African American schools included eleven elementary schools, one high school (Kortrecht, founded in 1890), two post-secondary institutions (LeMoyne Normal Institute organized by the American Missionary Association in 1871, and Howe Institute established by African American Baptists in 1900), and the University of West Tennessee with departments of medicine, law, dentistry, pharmacy, and nursing. African Americans were also active in Memphis political life from the 1870s through the 1890s. Two black men served on the Board of Common Councilmen in 1872, four in 1873, and six in 1874. Blacks continued to serve on the council until 1879. African American voting power was diluted during much of the Taxing District period: from 1879-1892, when debt, corruption, mismanagement, and two deadly yellow fever epidemics forced the city to surrender its municipal charter to the State of Tennessee. The Taxing District was governed by a Legislative Council made up of the members of the Fire and Police Commission, the Public Works Commission, and the Board of Health. The governor appointed two of the Fire and Police Commissioners, although one was later appointed by the Shelby County Quarterly Court. Taxing District residents elected the third commissioner. Residents of the Taxing District elected three of the supervisors (commissioners) of Public, one was appointed by the governor, and one selected by the Shelby County Quarterly Court. No blacks served on the boards until Lymus Wallace was elected to the Board of Public Works in 1882 and served until 1886. He was the city's last African American elected official until 1964.

Fourteen African Americans were elected to the Tennessee General Assembly in the 1880s and 1890s; five of the fourteen represented Shelby County and most resided in Memphis. Attorney Thomas F. Cassels and businessman Isaac F. Norris represented Shelby County in the 42nd Tennessee General Assembly, 1881-1882; hotel porter and janitor Leon Howard served 1883 - 1884; former teacher, mail agent, and wharf-master Greene E. Evans served 1885-1886; and William A. Field, a farmer, school teacher and justice of the peace served in 1885-1886.

At least four black newspapers circulated in the city between the 1870s and the 1890s. The most famous was the Free Speech and Headlight owned by Reverend Taylor Nightingale and J.L. Fleming. School teacher and journalist Ida B. Wells wrote for and later purchased a one-third interest in the newspaper. In the 1880s, the editors criticized the expansion of segregation and the disfranchisement of African Americans in the city. The Free Speech and Headlight began publishing Wells' anti-lynching articles including those commenting on the 1889 lynching of three black businessmen in Memphis. Wells went on to publish pamphlets detailing violent attacks on African Americans and encouraging black Memphians to leave the city. In 1892, the offices of the Free Speech and Headlight were destroyed and Wells, who was out of the city when the attack occurred, was threatened. She did not return to the South for over thirty years.