Fayette Timeline 1960

January 31, 1960

Source: Wikimedia Commons. Available under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike license. |

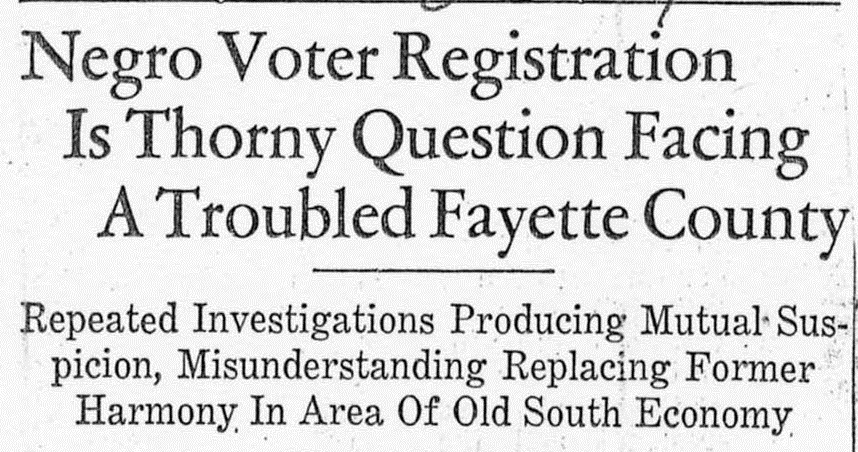

The Civil Rights Commission officials ask to inspect Fayette County voter rolls in order to investigate the allegations of disenfranchisement. In an attempt to stall the investigation as well as keep black citizens from registering, the county's election commission resigns.

Estes plays a pivotal role in having John McFerren and Harpman Jameson, leaders of the Fayette County movement, and Currie Boyd, a leader of the Haywood County movement, attend the Volunteer Civil Rights Commission hearings chaired by Eleanor Roosevelt in Washington, DC on January 31, 1960. Moreover, Estes writes and publishes a newsletter, The Times Herald, which focuses on local struggles by African Americans in West Tennessee for civil rights. Understanding the increasing power of media to inform persons across the nation and the world about local struggles for civil rights, he often travels with famed photographer Ernest B. Withers, who is later hired by Fayette County activists to capture significant moments in the civil rights movement as they unfolded throughout the 1960's.

March 15, 1960

Source: The Commercial Appeal: March 30, 1960, Special Collections, University of Memphis Libraries

The white citizen's council in Fayette County compiles a list of African Americans who register to vote, called the "blacklist." This list is provided to white business owners in the county with the understanding that they will not sell goods or provide services to those African Americans whose names appear on the list. The blacklisting of registered voters results further in evictions of Black families from white farms. Many of these families have sharecropped on the same farm for decades.

The evictions take place with such speed and in such great numbers that many families' only option is to live in tents on the farms of two black landowners, Shepard Towles and Gertrude Beasley, who bravely offer their land for housing to the evicted sharecroppers.

The few white citizens who dare stand against the blacklisting are themselves boycotted and are shunned by other white citizens in the county. O.M. and Sara Lemmons refuse to participate in the boycott and give aid to blacks affected by it. Sara even testifies to the Justice Department retaliation in the county. Because of their stance and their generous giving to the boycotted blacks in Fayette County, the Lemmons eventually lose their garment business.

April, 1960

Source: Photo of John McFerren. Cleveland Call and Post, August, 1960 |

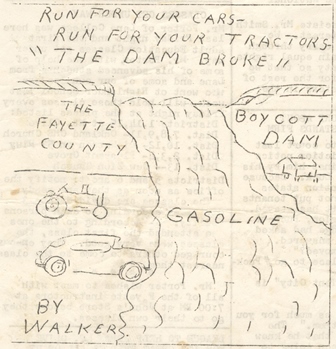

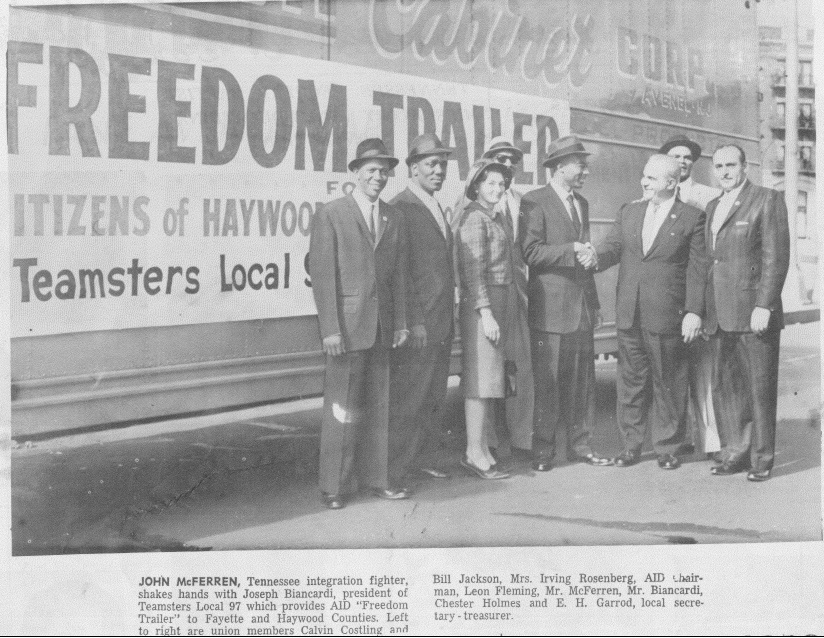

The economic squeeze continues, and John McFerren rents his brother Robert's grocery store in an effort to provide relief to those African Americans who have been blacklisted. Robert ceases operating the small grocery because white supremacists retaliate against him early on, incorrectly believing that he, rather than his brother, John, had instigated the voter registration among blacks. Like his brother, John is unable to receive deliveries and must drive to Memphis or pull over delivery trucks, buying goods directly from truck drivers to stock his store.

In 1960, McFerren secures a private loan from sympathetic white friends in Louisiana and later a loan from the Small Business Administration to build a larger grocery store a few yards from his brother's grocery. This second building serves as a meeting place for demonstration marches, reporters, and activists from across the nation, and thrives as a business serving primarily the African American community

John McFerren Talks about Problems Getting Gasoline

2002 documentary project on Fayette County, TN: Special Collections, University of Memphis Libraries

April 25, 1960

Source: Photograph, Special Collections, University of Memphis Libraries.

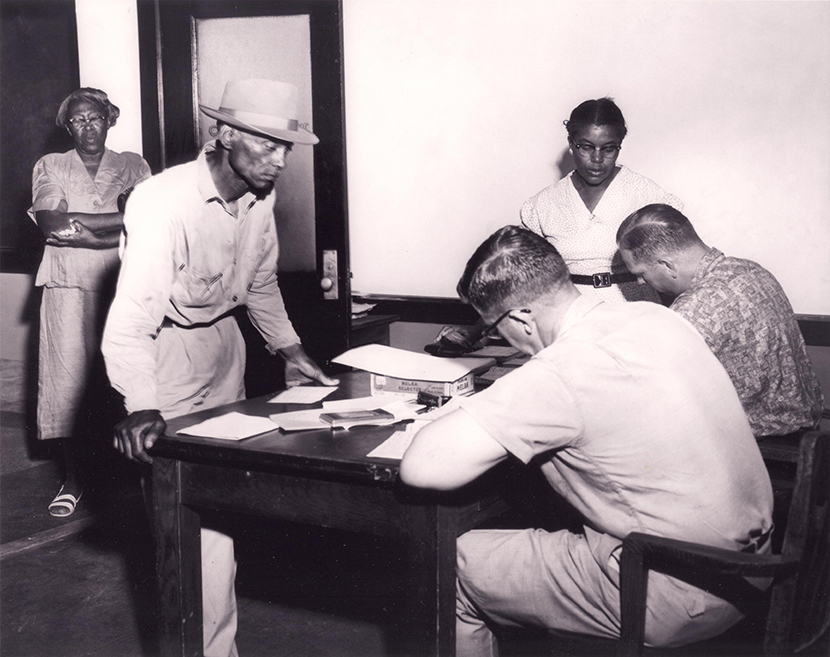

The federal government is finally able to end the boycott by election officials in Fayette County, and voter registration begins again through a consent decree in United States v. Fayette County Executive Committee. Registration only opens on Wednesdays, and Black citizens are forced to stand in line for hours in high temperatures to vote, some even fainting. On the other hand, white citizens who wish to register to vote are able to show up, register, and leave within a matter of minutes. Whites and courthouse employees harass Blacks by throwing hot coffee and pepper, or spitting on them. At this point, only 1,000 of the 9,000 voting age adults have registered to vote.

August, 1960

Source: ©Dr. Ernest Withers, Sr. courtesy of the Withers Family Trust

Ted Poston writes an exposé on Fayette County in the New York Post, bringing the local movement national attention.

Charlie Butts Tells How Ted Poston Influenced Him

2002 documentary project on Fayette County, TN: Special Collections, University of Memphis Libraries

August, 1960

Source: League Link Newsletter, April, 1961

After pressure from the NAACP, Gulf, Esso, Texaco, and Amoco oil companies break the fuel and gas embargo on black citizens in the county. This is a huge hardship for the people of the county who rely on the fuel to run, not only their cars, but also their farm equipment. John McFerren tries to procure gasoline for his store, but the only person who is willing to provide him with gasoline is threatened by the Sheriff.

September, 1960

Source: Photograph, Special Collections, University of Memphis Libraries |

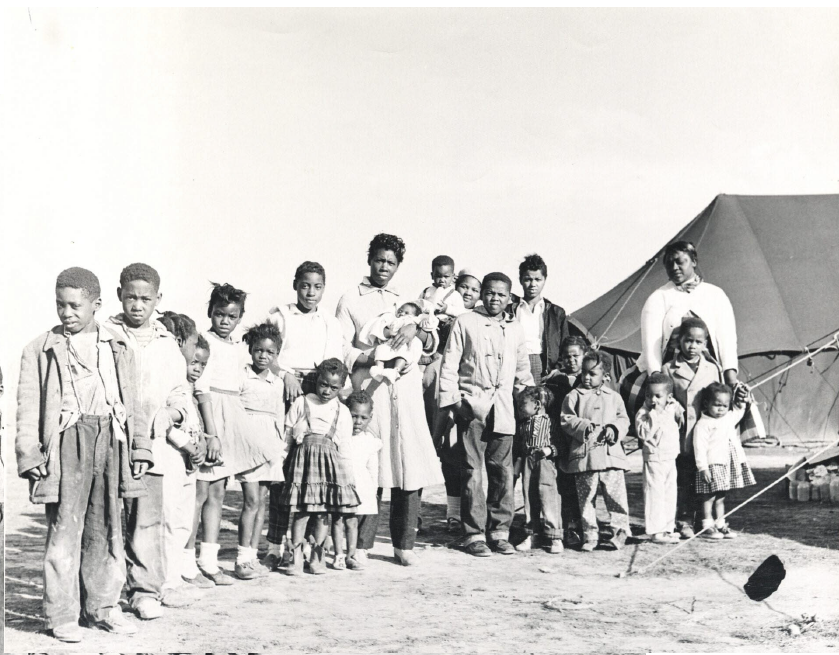

Eight black families are forced off land owned by Ellis Watkins, Bynum Leatherwood, and Mrs. Henry McNamee. Although far from wealthy, Shepard Towles, a black farmer who owns his land [located on Old Macon Rd (now Rhea Drive and Highway 195)], permits evicted families to pitch tents to live in. This collection of makeshift homes comes to be known as "Tent City." The extra demand for water eventually runs the Towles's water well dry, and his land can no longer accommodate all the evicted families. As a result, Gertrude Beasley, a black landowner with meager resources (located 4 miles east of Moscow, Fayette County,TN), opens up her land to pitch additional tents for evicted families. An anonymous white business owner donates many of the tents.

The evicted residents are further burdened with the inability to obtain basic necessities, including gasoline and food, and services, including medical services, because they are blacklisted for exercising their right to vote. At the height of evictions, approximately 13 families with more than 100 children are living in Tent City, some of the families living in tents for more than two years.

November 8, 1960

Source: Norfolk Journal and Guide: December, 1960

African-American registered voters turn the county Republican for the first time since Reconstruction. In keeping with Black historical allegiance to the party of Lincoln, many Fayette County Blacks register in 1959 and 1960 as Republicans. Like African Americans across the nation, Fayette County's black allegiance shifts when the Democratic Party and President John F. Kennedy's administration embraces a progressive stance on civil rights.

December 1, 1960

Source: Found on Wikimedia. Property of U.S. Government. The use of this photos does not indicate that the photographer, publisher, owner, copyright holder, or any other affiliate endorses this website, The Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change, or The University of Memphis. |

The U.S. Department of Justice Files United States v. Atkeison, Civil Action No. 4131, requesting preliminary injunctions against the retaliatory evictions of Fayette County sharecroppers. Attorney John Doar, First Assistant to Assistant Attorney General, Civil Rights Division, visits Fayette County to investigate the issues arising in this case. The case is paired with Haywood County's United States v Beaty, 288 F2d 653, Civil Action No. 14433, in which the Department of Justice seeks court action to stop evictions in Haywood County. The case is heard by Judge Marion Boyd, who denies the request. The case is appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, which orders Judge Boyd to institute and enforce the temporary injunction. (Originally, however, the circuit court refuses to consider Fayette County's complaint and rules solely on the Haywood case. In April of 1961, the decision is expanded to include both counties). On July 26, 1962, both cases are settled under a consent agreement, which declares that no party admits guilt, but all parties agree not to deny service to or evict African Americans in order to discourage them from registering or voting. In an effort to avoid flagrantly violating the agreement, white landowners begin evicting sharecroppers based on seemingly innocuous reasons, such as mechanization or poor work performance.

Charlie Butts Talks about Meeting John Doar

Interview conducted in 2002 by Robert Hamburger and Daphene McFerren. Property of Special Collections, University of Memphis Libraries.

December 14, 1960

Source: Photograph, Special Collections, University of Memphis Libraries.

The Department of Justice files suit seeking an injunction to prevent sharecroppers from being evicted for registering to vote. Judge Marion Boyd issues the injunction, but citizens in the counties are disappointed with how little help the injunction actually provides. On the same day as the filing, evicted sharecroppers begin moving into tents.

December 28, 1960

Source: Photograph, Special Collections, University of Memphis Libraries

Shots are fired into tents at the Towles farm site. One hits Early B. Williams in the tent he has been living in with his wife and children and barely misses hitting his infant child. No one ever faces criminal action.

December 30, 1960

Source: The Times Herald, Special Collections, University of Memphis Libraries, Memphis TN.

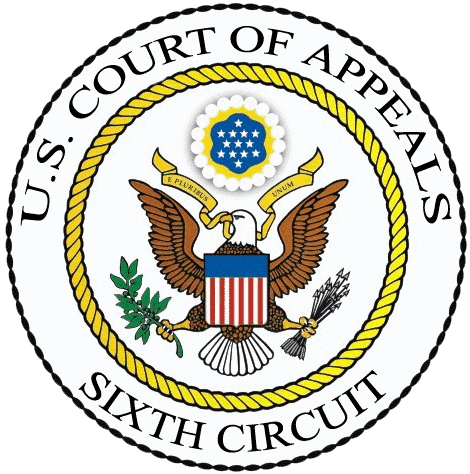

The local Red Cross refuses to provide supplies and emergency aid to Fayette County black citizens, claiming that the aid is not needed. However, a few other organizations, including The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organization (AFL-CIO), The United Automobile Workers (UAW), and the Teamsters, step in to help. During the same month, Estes, McFerren, and Franklin travel to Washington D.C., New York, and Chicago to request aid. They return with donations to help the people affected by the blacklist. The Unions view the plight of black farmers are connected to the goals of workers across the nation to obtain fair treatment and fair wages for their work.

Source: Devinatz, V. G. (2006). "To Find Answers to the Urgent Problems of Our Society: The Alliance for Labor Action's Atlanta Union Organizing Offensive, 1969-1971." Labor Studies Journal, 31(2), 69-91.