2004-2005 Season Report

Introduction

Our field work was authorized by Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities and functioned with the cooperation of the Centre Franco-égyptien pour l'étude des Temples de Karnak. We extend our thanks to our other Egyptian and French colleagues: Dr. Zahi Hawas, President of the SCA, along with the entire Permanent Committee which authorized our work. In Luxor, we are grateful to Mr. Ibrahim Sulliman, the Director of Karnak and Mr. Fawzy (our inspector); along with Nicolas Grimal and Emanuelle Laroche (scientific and field directors of the Centre). The expedition staff for this season's work included two epigraphists: the field director, Dr. Peter Brand of the University of Memphis, Tennessee and Dr. Suzanne Onstine from the University of Arizona. Three University of Memphis graduate students, Mrs. Louise Cooper, Mr. Robert Griffin and Ms. Heather Sayre also participated.

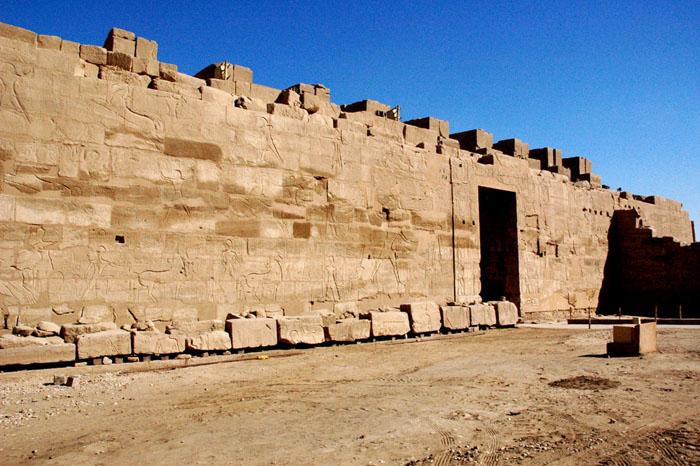

The Main focus of our work during the 2004-2005 field season: The south wall of the Hypostyle Hall with war scenes of Ramesses II.

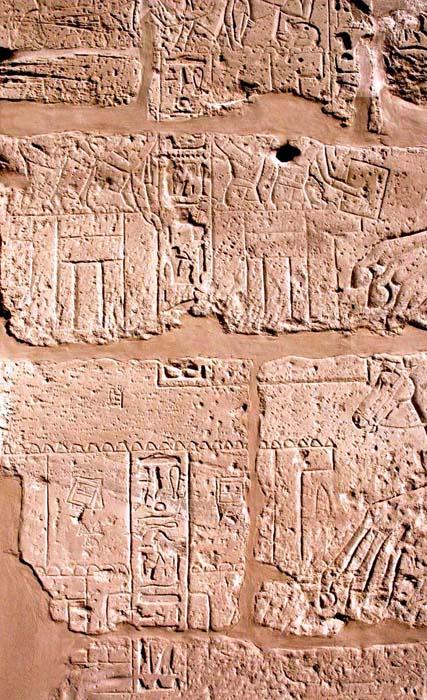

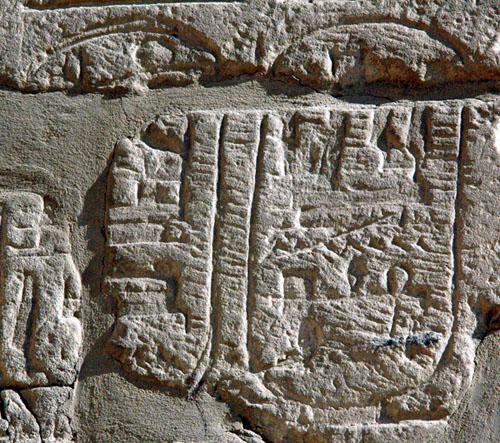

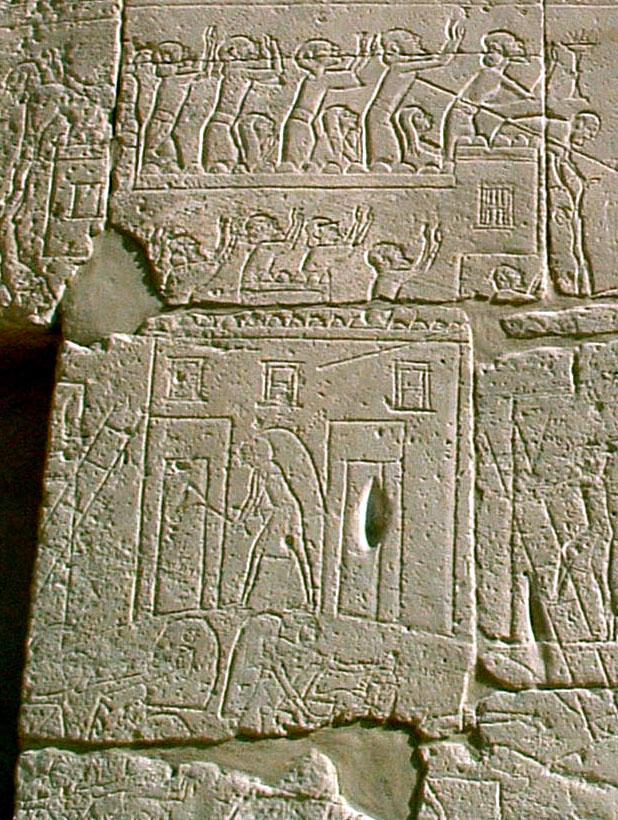

Each war scene on the south wall shows the king attacking two stereotyped towns. The name of each town is written in a column of text in its center.

Collation of Facsimile Drawings of the Battle Reliefs of Ramesses II on the South Wall with Palimpsest of the Battle of Kadesh

The main objective of the season was to complete collation of war scenes on the south exterior wall of the Hypostyle Hall in order to produce facsimile drawings of these reliefs. Initial drawings of these war scenes were first made in 1995. We began collation of the drawings in 1999 under the Project's late director, professor William J. Murnane. Our collation of the inscriptions on this wall was made more difficult by their poor state of preservation and the fact that part of the wall is a palimpsest in stone with two sets of hieroglyphic texts superimposed one atop the other. After getting bogged down in the palimpsest in 2000 and 2002, we were finally able to complete our record of the south wall in the 2004-2005 season. Despite moving beyond the area of the palimpsest, our work remained especially challenging due to the severe erosion that much of the wall suffers from as well as the fact that many parts of the wall were so poorly dressed by the sculptors that much of the relief was carved in plaster or in some cases patching stones that have since fallen away.

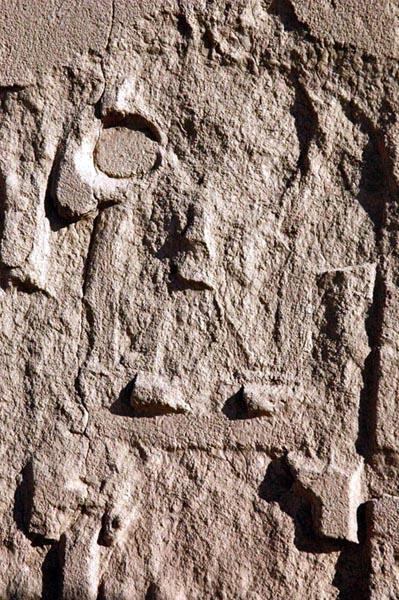

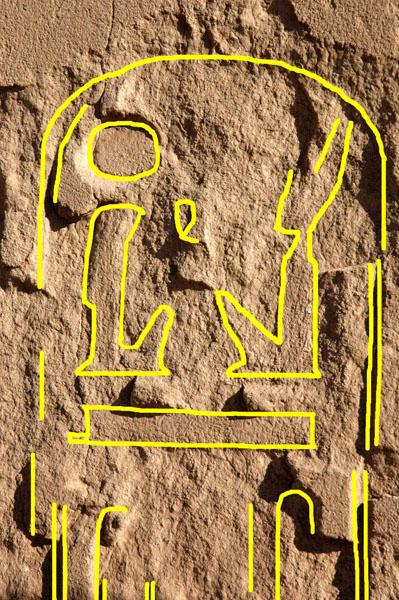

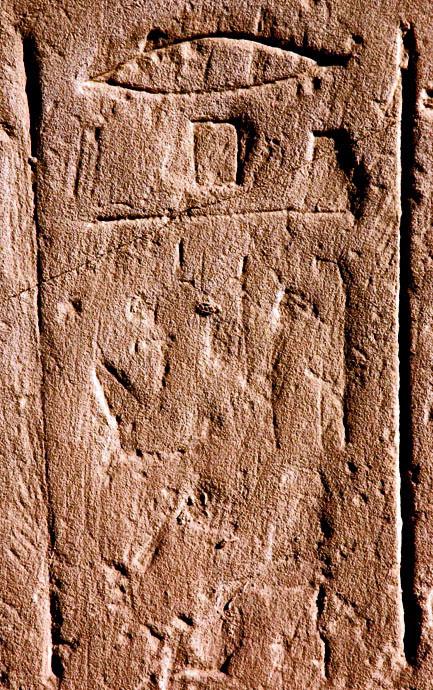

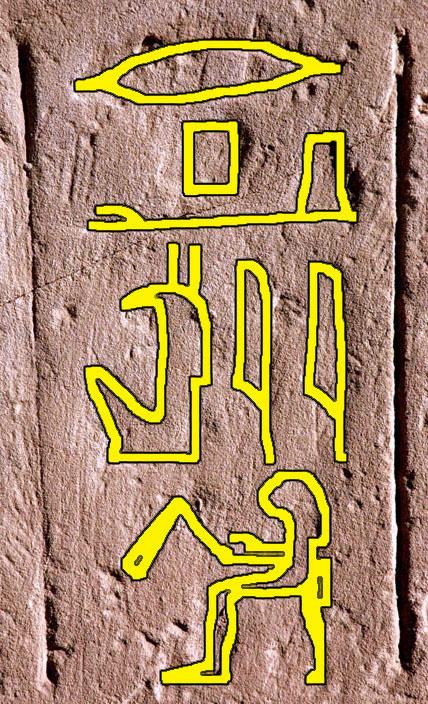

A badly eroded cartouche of Ramesses II. The lines in yellow on the right indicate the traces of the name that could still be read. This level of erosion was typical of the poor condition of the wall in many places.

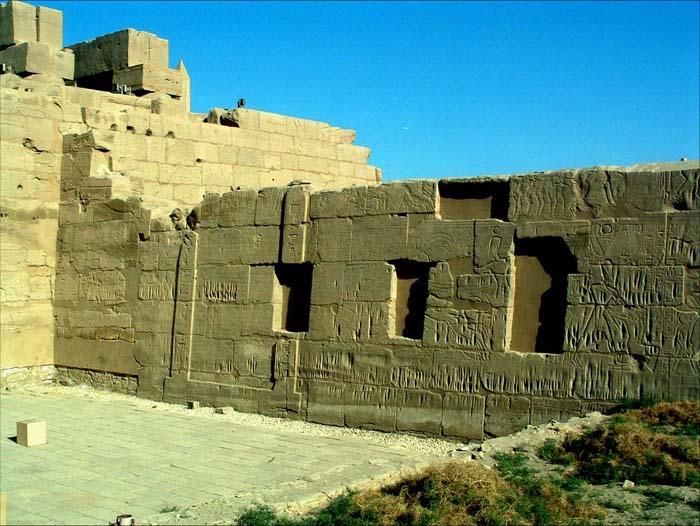

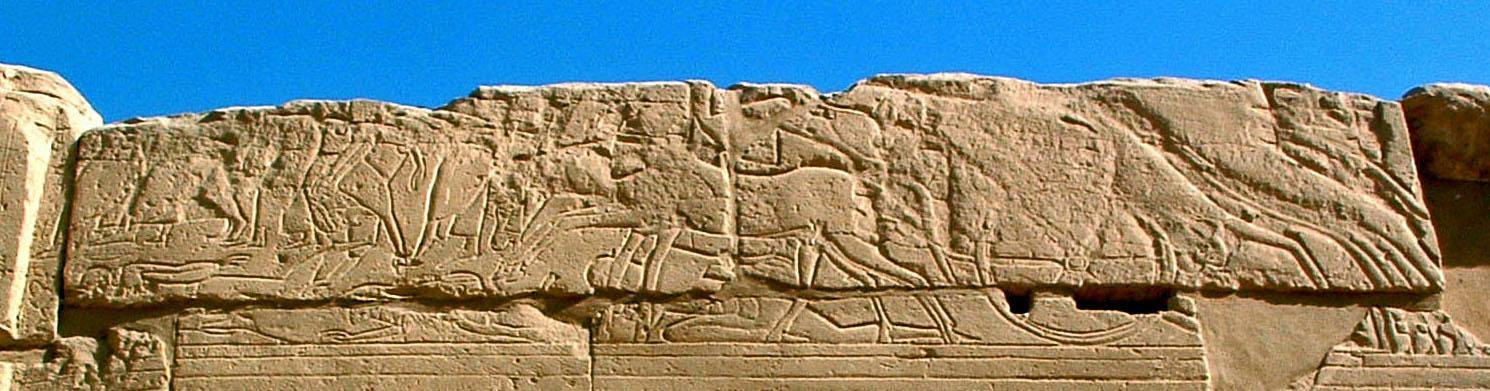

War scenes on the west exterior wall of the Cour de la Cachette. At the extreme left the wall abuts the south wall of the Hypostyle Hall.

The Chronology of War Scenes on the South Wall of the Hypostyle Hall and the Adjoining Wall of the Cour de la Cachette

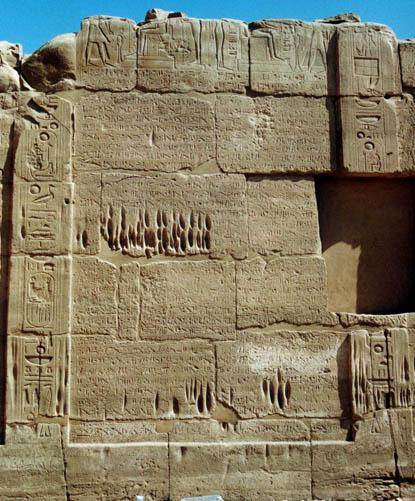

For several years now, a major focus of the Hypostyle Hall Project's scholarly endeavors has been to date accurately the reliefs inscribed on its walls and, sometimes, on adjacent monuments. The west wall of the so-called Cour de la Cachette at Karnak intersects the south wall of the hypostyle. The exterior face of the west wall is inscribed with war scenes of a character very similar to those on the south wall of the Hypostyle. For decades Egyptologists assumed that the Cour de la Cachette war scenes were part of the same series as those of Ramesses II on the south wall. In fact, like the south wall of the Hypostyle, there is also a palimpsest on the west wall of the court. The earlier edition of the palimpsest consisted of a panorama of Ramesses II's famous Battle of Kadesh pictorial narrative. This was never completed, perhaps because of the aesthetic compromise of having to bend the reliefs "around the corner," and so work was abandoned and the unfinished Kadesh narrative was partially erased and both walls were reused for later war scenes.

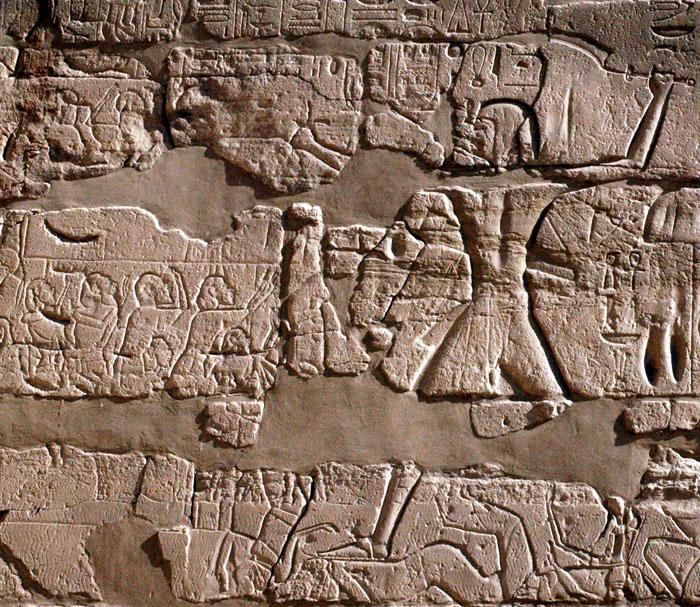

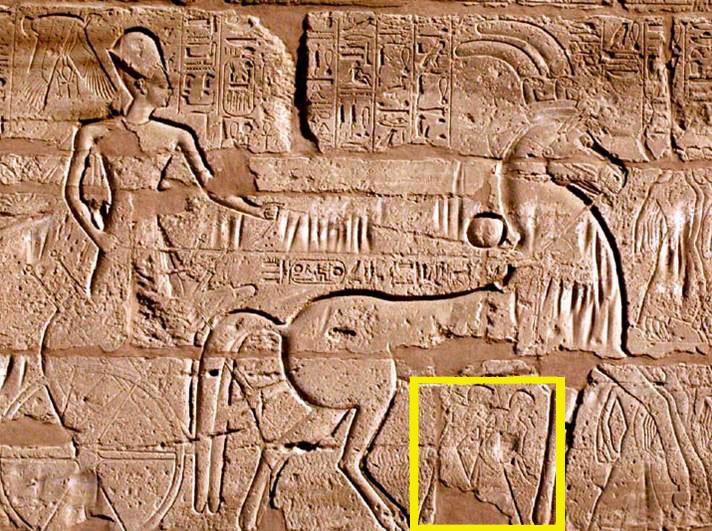

Merenptah storms a fortified town. Cour de la Cachette, west exterior wall, north end. Wavy vertical lines along the base of the scene are a palimpsest of the river Orontes from the erased battle of Kadesh reliefs of Ramesses II.

In the mid 1980s, the late Frank Yurco of the University of Chicago proposed that the later editions of the war scene palimpsests on the south wall of the Hypostyle and the west wall of the Cour de la Cachette were not, as had always been assumed, part of the same composition but that the latter were made by Merenptah, the son and successor of Ramesses II.1 Ramesses was, therefore, only responsible for the final relief decoration on the south wall of the Hypostyle. Yurco's findings were very controversial given that he also proposed that Merenptah's war scenes on the west wall gave a pictorial representation of a battle he fought with a people named on a victory texts of his reign— namely the Israelites!2 The Victory stela of Merenptah is the earliest extra-biblical reference to the Hebrew people and if Yurco was correct then the reliefs preserved the earliest image of the same. This was extremely controversial and was made more so by the condition of these war scenes.3

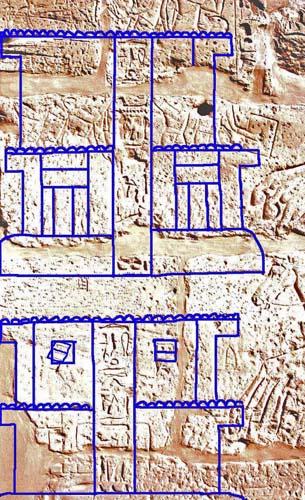

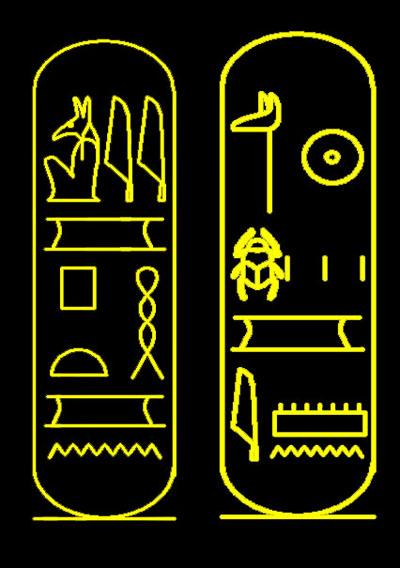

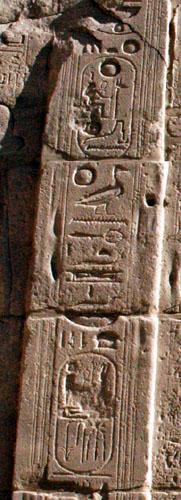

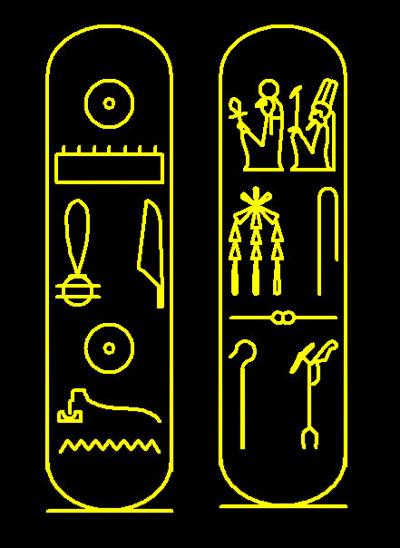

Top Left: Merenptah cartouches

Top Right: Sety II Cartouches

Bottom: usurped cartouches from the Cour de la Cachette battle scenes. Traces of Both king's names were found in these usurped cartouches. Neither Ramesses II nor Amenmesse ever carved there name here.

The Cartouches, i.e. royal name rings, on the west wall gave the name of pharaoh Sety II, Merenptah's successor. But these had obviously been tampered with because the glyphs in the cartouches had obviously been altered and the name of an earlier pharaoh— Merenptah— were in some cases clearly legible. No one doubted that the name of Merenptah had been altered, but some argued that there was an even earlier name that had been erased— Ramesses II. Yurco's opponents maintain that the name of Ramesses II had originally graced the war panorama on the west wall and that these had been successively usurped by as many as three later pharaohs: Merenptah, then Amenmesses, and finally Sety II. No trace of Ramesses' name has been found in any of the war scenes, although his name occurs in a marginal text and in a royal stela which bisects the war panorama.

Hittite Peace Treaty stela of Ramesses II. The king's names were never altered or usurped, although there is some random damage to the cartouches as can be seen in the detail of the left side frame of the stela.

Although scholars have put forward various historical and textual evidence and reasoning for why the Cour de la Cachette war scenes are or are not to be dated to Merenptah's reign, the reliefs have not been subjected to the thorough epigraphic and art historical analysis that might finally resolve the issue. Working closely with the south wall reliefs for months at a time as we recorded them and being daily close by the Cour de La Cachette reliefs, the present writer has had the opportunity to investigate the epigraphic and historical puzzle of these two sets of inscriptions. My observations of these have led me to conclude that Yurco's dating of the west wall reliefs to the reign of Merenptah is correct. The same cannot be said for his conclusion that the Israelites appear on this wall since the name of pharaoh's opponents is missing in the scene Yurco identified as that showing the Israelites.4

The earliest Representation of the Israelites? Only the lower 1/3 of a scene showing pharaoh attacking a group of Canaanites survives. The name of these people, who some think are the Israelites, would have been recorded near the top of this poorly preserved relief. The earliest textual reference to the Israelites is found on the victory stela of pharaoh Merenptah who may have been the author of these scenes.

Biblical polemics aside, our historical interests in these scenes has more to do with the internal history of the Late Nineteenth Dynasty and with the military career of Ramesses II. It is now clear that we cannot include the wars shown on the west wall as part of Ramesses II's military exploits in the Levant. The west wall tells us much, however, about the internal history and chronology of Egypt in the years after his death and that of his successor Merenptah. Having produced as many as 50 royal sons, Ramesses II's dynasty fell into civil war as two or more lines of his family battled for control of the throne. Merenptah's successor, Sety II was challenged by an interloper named Amenmesse, a member of a cadet branch of Ramesses' huge family.

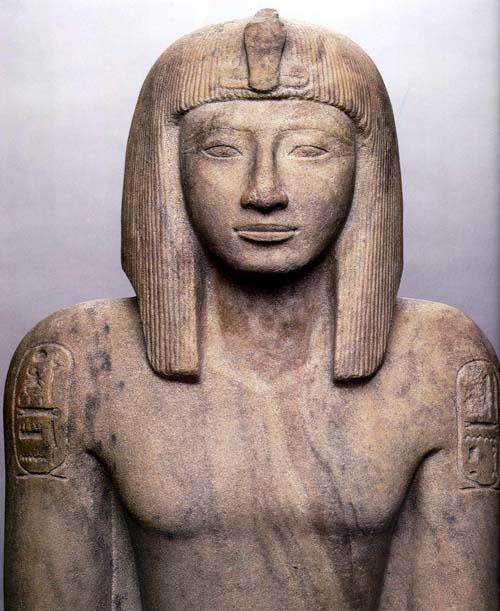

Left: head of Amenmesse (New York MMA 34.2.2) Right: Sety I (London British Museum EA 26)

Amenmesse seems to have taken control of Upper Egypt after Merenptah's death and remained there for less than five years until Sety II asserted his rightful claim to this part of his realm. During his brief flourit, Amenmesse's main accomplishment was to supress the name of Merenptah on the latter's monuments in Upper Egypt including those at Karnak. When Sety II reclaimed Upper Egypt he replaced the erased name of his father with his own. Nearly everywhere one sees Sety II's names at Karnak, it is carved in a small depression where his father's name had previously been erased. A puzzling conundrum had troubled scholars of this period, because in no case are traces of the name of Amenmesse found in these erased cartouches. One would expect that, as with other pharaonic usurpers, that Amenmesse would have replaced the erased name of his despised predecessor with his own. Yurco thought he had found a small trace of Amenmessesin one cartouche on the west wall, but this proved to be a phantom when this and other cartouches were checked. No trace of Ramesses or Amenmesse was found in any case where Sety II's name had been inserted over the erased name of his father. Perhaps Amenmesse painted his name in these erased cartouches of Merenptah, but he did not carve it there.

Amenmesse's Cartouches. No trace of them have ever been found over the erased name of Merenptah at Karnak or Luxor.

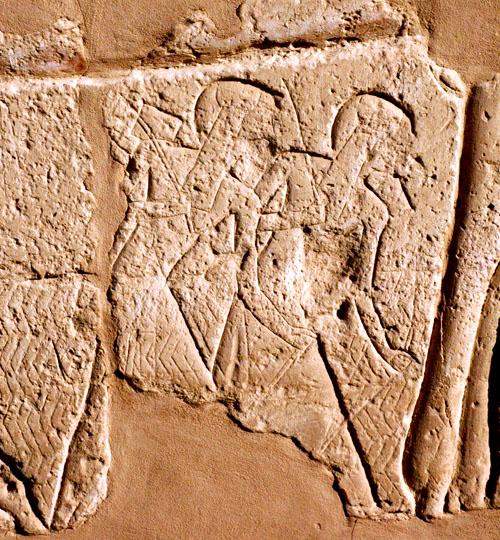

Crown Prince Sety riding in a chariot equipped with a sun shade. The Prince's name has been partly erased on the left side of the scene, but can still be made out.

This past season of work yielded the second of what we believe to be two "smoking guns" that prove that the west wall scenes were originally those of Merenptah and that Amenmesse simply erased his name without placing his own there. I had long been familiar with a block that obviously comes from the now partially dismantled war scenes on the Cour de la Cachette west wall. It shows a prince in a chariot whose name has been erased by smoothing back the surface. Traces of the original glyphs of the prince's name are legible when the block is inspected up close. In pharaonic times, however, with the erased name painted and plastered over, it would not have been apparent. The prince is entitled "Heir Apparent" and his name is Sety. He is, I believe, the future Sety II. Another prince named in these reliefs is one Khaemwaset. A well known son of Ramesses II by this name led Yurco's detractors to claim that this was evidence that Ramesses II was the author of the west wall reliefs, but Khaemwaset is a common Ramesside name. It is unlikely that the relativlely obscure prince Sety, a minor son of Ramesses II, was ever portrayed as a Crown Prince on his father's monument, and since there were a number of princes who became crown prince and died in sequence before Ramesses II was finally succeeded by Merenptah, it would be odd for Amenmesse or any other late Nineteenth Dynasty ruler to take umbridge with a long deceased princeling of Ramesses II. But if the defamed Crown Prince Sety was in fact the heir of Merenptah, Amenmesse had every reason to delete his name along with his father Merenptah's name form the monuments.

Detail of the erased name of Crown Prince Sety, the future Sety II.

Amenmesse's Defacement of Merenptah's Monuments and their Restoration by Sety II

As our work at Karnak continued apace in the fall of 2004, I was considering the epigraphic puzzle of the Cour de la Cachette war scenes. The final piece of the puzzle came into place when I inspected some erased marginal inscriptions at Luxor temple, a few miles south of Karnak. In the Ramesside court, Merenptah had added a horizontal ribbon of his names and titulary in the dado of the walls. This had been erased throughout, although not carefully, so that clear traces of the name shone through. Merenptah's names and titles were clearly apparent. But whoever had done this had not chosen to expropriate the inscription for themselves as was common practice. Rather, he simply deleted the whole text by smoothing it away. Here we have, I believe, an explanation for what was going on at Karnak and the solution to an epigraphic problem, the absence of Amenmesses' name in any of the cartouches that he must have erased. Perhaps this eluded us because Amenmesses did not treat Merenptah's relief as we might have expected. Normally, pharaonic damnatio memoriae involved the violent hacking out of a predecessor's name or the careful erasure of it to be replaced with the usurper's name. One does not expect the careful erasure without replacement we find with Amenmesses' treatment of Merenptah's name. But the marginal texts at Luxor and the erased name of Crown Prince Sety shows that Amenmesses did just that.

Top: An erased cartouche of Merenptah from Luxor Temple. Bottom: The cartouche of Merenptah as it originally appeared. Merenptah's entire inscription was erased by Amenmesse, but he never replaced it with his own. This confirms what the evidence at Karnak had suggested, that Amenmesse removed Merenptah's name from the monuments without replacing it with his own. Since the Luxor Temple inscription was completely erased- not just the cartouches- Sety II never restored it in his own name.

Differences Between the Hypostyle Hall War Scenes of Ramesses II and those of Merenptah on the West Wall of the Cour de la Cachette

Further close scrutiny of both sets of war scenes elicits further epigraphic and art historical evidence that they were made at different times by Ramesses II and Merenptah respectively. On the south wall of the Hypostyle Hall, for example, the king is always shown attacking two fortresses one "stacked" atop the other according to the conventions of Egyptian art. Each fortified town appears the same in a "cookie cutter" fashion (see above). On the west wall, the forts are more elaborate where they appear— one per scene— while in two other scenes, the king attacks foes in open country with no settlement present. Other motifs distinguish the two sets of reliefs. The west wall of the Cour de la Cachette includes princes and other Egyptian soldiers participating in the melee, while on the south wall, Ramesses fights alone and the only other Egyptians shown are a pair of royal bodyguards or groomsmen by the king's horse as he returns in triumph with enemy prisoners.

Egyptian soldiers assaulting Ashkelon from the reliefs of Merenptah on the west wall of the Cour de la Cachette. An Egyptian soldier batters a gateway. The presence of Egyptian soldiers and princes and the elaborate depiction of the walled town differs strikingly from the reliefs of Ramesses II on the south wall of the Hypostyle Hall.

South wall of the Hypostyle Hall: The only Egyptians in any of Ramesses II's war scenes are a pair of royal bodyguards (bottom) who only appear in the king's triumphant march back home to Egypt.

Conservation of Sandstone Blocks from the Karnak Hypostyle Hall

Conservator Edwige Bussi performed conservation and restoration of several blocks from the Great Hypostyle Hall at Karnak during February of 2004 . This work was carried out under the supervision of the SCA and the Franco-Egyptian Center at Karnak. The work was done on behalf of the Karnak Hypostyle Hall Project and its director, Dr. Peter Brand, of the University of Memphis. All costs were paid by the Karnak Hypostyle Hall Project of the University of Memphis, Tennessee, USA.

The Karnak Hypostyle Hall Project hopes to resume conservation work in the fall of 2005 once additional funds for this work are obtained through the American Research Center in Egypt's Egyptian Antiquities Project or through some other granting agency in the United States. The following report describes the work on several blocks done by Mrs. Bussi in February 2004 and on the condition of some others that still need to be conserved. A total of nine blocks were conserved and in some cases reassembled from fragments.

A block from the north wall of the Hypostyle Hall. Several fragments were conserved and then reassembled in early 2004. It shows the kneeling figure of the king.

Procedures Used to Treat the Blocks

Treatment

The blocks were treated with ethylene silicate (Wacker OH - diluted with Xylene from 50% -100% - depending upon the state of disintegration of the sandstone). Loose fragments were treated by soaking in a container for between ten minutes to two hours (depending on the size of the fragment), and then covered with paper and clear plastic for two to three weeks. Fragments in situ were treated by the application of the chemical compound with a large brush, and were then covered with paper and clear plastic for two to three weeks. Inaccessible joints were treated by injecting silicate with a syringe, and by then covering them with paper and clear plastic for two to three weeks. Inscribed surfaces were protected by a liquid adhesive (5% Gelvatol in water) that would not interact with the silicate, and that would help to limit the darkening of the stone.

Reassembly

Cracks and other gaps were filled with Araldite AY 103 (diluted to 80% with acetone) injected with a syringe. The surface area was then protected by a liquid adhesive (5% Gelvatol in water) in order to prevent the Araldite AY 103 from penetrating the surface. Large fragments were saturated on the side to be remounted with Araldite AY 103 (diluted to 80% with acetone) using a sponge. Araldite 2015 was then applied to the corresponding surface of the main block, and the fragments were remounted and held in place by straps for twenty-four hours. Small fragments were saturated with Araldite 2015 before being remounted and held in place using manual pressure.

Cleaning and Removal of Salts

Salts were removed with a brush and paper poultice using ammonium carbonate (diluted to 10% with water). The chemical treatments were then rinsed away using water for the Gelvatol, and clay moistened with Xylene or acetone for the silicate and Araldite, where these had impregnated the surface.

A block with a large hieroglyph of a duck from the north wall of the Hypostyle Hall. It was reassembled from several fragments in 2004.

Notes

[ 1↑] For our more recent assessment of the war scenes on the south wall of the Great Hypostyle Hall and their relationship to those on the western wall of the Cour de la Cachette see: Peter J. Brand, "The Date of Battle Reliefs on the South Wall of the Great Hypostyle Hall and the West Wall of the Cour de la Cachette at Karnak and the History of the Later Nineteenth Dynasty," in M. Collier and S. Snape (eds.), Ramesside Studies in Honour of K.A. Kitchen, (Bolton: Rutherford Press Limited, 2009), pp 51-84; Peter J. Brand, "Usurped "Cartouches of Merenptah at Karnak and Luxor" in P Brand and L. Cooper, (eds.), Causing His Name to Live: Studies in Egyptian Epigraphy and History in Memory of William J. Murnane, (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 2009), 29-48.

[ 2 ↑]Frank Yurco, "Merenptah's Canaanite Campaign," Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 23 (1986), 189-215; idem, "3,200-Year-Old Picture of Israelites Found in Egypt," Bibilical Archaeology Review 16, no. 5, (September/ October 1990), 20-38. In support of Yurco's overall theory but with slightly different perspectives on who the earliest Israelites were see: M. G. Hasel, "Israel in the Merneptah Stela," Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 296 (1994), 45-61; A.F. Rainey & F. J. Yurco, "Which Picture is the Israelites?: Anson F. Rainey's Challenge & Frank J. Yurco's Response," Biblical Archaeology Review 17, no. 6 (November/ December 1991), 54-61; I. Singer, "Merneptah's Campaign to Canaan & the Egyptian Occupation of the Southern Costal Plain of Palestine in the Ramesside Period," Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 269 (1988), 1-10; L. Stager, "Merenptah, Israel and the Sea Peoples: New Light on an Old Relief," Eretz Israel 18 (1985), 56-64.

[ 3 ↑]For a translation of the Israel Stela see M. Lichtheim, "The Poetical Stela of Merenptah (Israel Stela)," Ancient Egyptian Litterature, volume II, (Malibu, 1976), 73-78.

[ 4 ↑]A number of scholars have challenged this theory. See especially D. B. Redford, "The Ashkelon Relief at Karnak and the Israel Stela," Israel Exploration Journal 36 (1986), 188-200; idem, Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times, (Princeton, 1992), 241-249 & 263-280.

Amenmesse's Defacement of Merenptah's Monuments and their Restoration by Sety II

Conservation of Sandstone Blocks from the Karnak Hypostyle Hall